Apple Storage

Improving apple storage technology has extended the availability of fruit in the domestic market and facilitated export – a story of evolution and innovation.

Apples have a limited life once they have reached eating maturity. This is because once ripe, they are physiologically programmed to deteriorate and become unpalatable very quickly.

Varieties extend the marketing season

In the early days of the apple industry in SA growers used a wide range of varieties with different maturity dates to maintain some sort of continuity of supply to the markets. Early Department of Agriculture publications list as many as 15 commonly grown varieties which ripened early, mid season and late (eg E Hawke (1912) in a paper for the Uraidla and Summertown Agricultural Bureau). Within such a group of varieties were those that had a short shelf life to be consumed soon after picking, and those that would remain palatable when stored at or near room temperature for many months. Eventually even these became unpleasant to eat and apples were then not available until the next season.

Throughout the 20th century, the number of varieties grown reduced dramatically and was limited to a group suited to refrigerated storage. Towards the end of the 20th century some newer varieties with improved eating and storage qualities were introduced and these have changed the industry completely.

One way open for growers to take advantage of changes in varietal preference was to “rework” existing trees with buds of the more desirable varieties. Over the years there were a number of Department of Agriculture publications that described the available techniques, and tested their suitability (eg Wicks and later revisions by D. T. Kilpatrick and others)

Coolstores further extend the marketing season

The development of refrigerated coolstores in the early decades of the 20th century allowed the season to be extended until as late as Christmas time. Some varieties were found to perform better in cool storage than others, and the range of varieties grown in SA shrank considerably. Some of these were more suited to export markets (eg Rome Beauty and Cleopatra) and some to the local market (Jonathan, Delicious and Granny Smith).

Early stimulus for the development of cooperative and later private coolstores in SA came from the Department of Agriculture’s work and the Agricultural Bureaux movement. Papers were presented at Agricultural Bureaux meetings by local (probably) amateur specialists and by invited specialists (what we would call consultants, nowadays) such as D.A. Crichton (Horticultural Lecturer from Victoria) who presented a number of lectures in 1891. Reports of these lectures were widely distributed (10,000 copies) and published in the daily press. G.R. Laffer (1913) at a meeting of the Blackwood Agricultural Bureau called for the development of co-operative packing sheds and coolstores, and emphasised the importance of care with harvest maturity to ensure a good product .

The Balhannah Coolstore was the first to be built (in 1914). It was built by H.N. Wicks and Augustus Filsell. The structure was wood and the insulation sawdust. It was powered by a gas producer according to the Balhannah Cooperative web site. Balhannah became a company in the 1920s and a cooperative in the 1940s.

Further reading

Balhannah Co-op Soc Ltd Silver Jubilee Book 1970-71 ()

Others followed, and by the 1960s there was a network of private and cooperative coolstore societies located throughout apple production districts. See a full list of coolstores in the Apple Harvest Festival Program.

Further reading

Adelaide Hills Apple & Pear Festival brochure 1965 ()

With rationalisation of apple production to the central Adelaide Hills, and many larger growers building their own “on farm” cool store facilities, the number of cooperatives has now reduced. However, they still play an important role in storing, packing and marketing SA’s apple crop, and storing a range of other commodities requiring refrigeration. By 1967, Steed reported that the capacity of the co-operative coolstores was about 745,000 bushel cases and those in private hands about 256,000 cases. Annual production by then was above 1 million cases.

Development of export markets

Refrigeration also allowed apples to “live” long enough to be exported by ship to the northern hemisphere (particularly to the UK and Germany). Quinn (1912) noted that apple exports had grown from 647 cases in 1896 to 187,701 in 1911/12. By 1922 he noted that of the 2,000,000 cases shipped overseas in that year, as many as 500,000 to 600,000 cases arrived in Europe with brown heart. This was caused by the excessive build up of CO2 in the holds of ships leading in turn to a loss of about 250,000 pounds (currency). (These figures are believed to be for Australia as a whole rather than SA alone.)

The Government Produce Department played a key role in development of export apple markets. In his September 1908 annual report, George Quinn wrote:

“The overseas export of South Australian fresh fruit to European and other countries practically took its rise as a regularly established trade with the foundation of the Government Produce Department at Port Adelaide. The writer has been actively connected with the trade since its inception in 1896, when with the assistance of the first manager of the depot (Mr E.J.B. Ebdy) a circular embodying general instructions to growers was formulated respecting the selection and packing of apples for export. This circular supported by many personal interviews, which were not always of an appreciative nature – resulted in several small consignments being dispatched in that year.”

Post-harvest disorders limit storage life

Problems with poor out-turn of export fruit led to the development of the whole new science of post harvest physiology, and Australia and New Zealand became leaders in this field through the CSIRO laboratories at Sydney University and later North Ryde.

The first disorder that was focussed on nationally was known as Bitter Pit. Black spots appear on the surface of the fruit and in the flesh both on the tree and after various periods in storage. These make the fruit unattractive, unpleasant to eat and eventually unsaleable. In 1912 Professor D. McAlpine, a plant pathologist from Victoria was asked to prepare a report for the Commonwealth and the State governments as to whether bitter pit was an infectious disease. It was much later shown to be a physiological disorder caused by a deficiency of calcium in the fruit which could partly be offset by application of calcium sprays to the trees, and changed pruning techniques to minimise the competition between the growing shoot and the fruit. (D.H. Simons, SA Journal of Agriculture mid 1960’s ).

The impact of high CO2 in the holds of refrigerated ships on their way to Europe leading to the disorder now known as brown heart has already been mentioned.

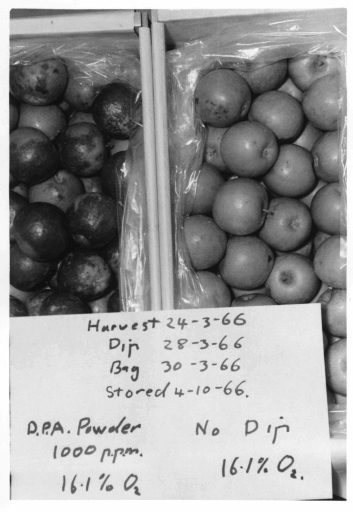

Superficial scald was another disorder that severely reduced the value of fruit that had been in coolstore. Wrapping fruit in paper impregnated with diphenylamine (DPA) was initially used until automated packing lines were developed and then dipping in DPA became the norm for susceptible varieties.

Early experiments to use DPA for control of scald – Blackwood Orchard, October 1966.

The variety Jonathan became the most important variety grown in SA. It was found to have it’s own problems as it is susceptible to a disorder known as senescent breakdown (John Steed, 1969). Fruits became brown and mushy and were said to be “sleepy”. This problem was seen more frequently in large fruit (eg from the off crop year) and some growers managed their trees to crop every other year to ensure crops of small fruit which were likely to store better.

Controlled atmosphere (CA) storage further extends the marketing season

The post harvest physiologists were able to show that storage disorders could often be minimised by close management of the temperatures at which the fruit was stored, and by manipulation of the composition of the atmospheres in which they were stored. However one size did not fit all with different varieties behaving differently when stored under modified atmospheres. W.B. McGlasson wrote a Bulletin on modified atmosphere storage in 1956 which included colour plates. B.L. Tugwell updated this bulletin in 1970 and it is interesting to see the changes in knowledge and the reduction in the number of varieties grown over that period.

Experiments in the new science of Controlled Atmosphere storage, first by J.V. Jacobsen, then by W.B. McGlasson of the SA Department of Agriculture (who subsequently joined the team at CSIRO North Ryde), and later by Barry Tugwell led to a better understanding of these issues for the major SA varieties of the time (Jonathan, Delicious, Golden Delicious and Granny Smith). This work was continued in to the 1990s by Barry Tugwell and his team with emphasis on some of the newer apple varieties (Gala, Fuji, Pink Lady® etc.).

Further reading

- Tugwell B. L.; (1970) Controlled atmosphere storage of apples and pears. South Australian Department of Agriculture Extension bulletin No 28/70

- Tugwell B. L.; (1997) Evaluation of Storage Performance and Storage systems for new Apple varieties. HRDC Final reports AP123 (1997).

Commercial equipment to generate low oxygen and elevated CO2 environments was expensive and Tugwell designed low cost gas fired alternatives. Lime-based CO2 scrubbers were also used to take out the excess CO2 generated by the respiring fruit. Conventional coolrooms were not sufficiently gas tight to maintain constant gas composition, so Tugwell worked with coolstore managers to develop the concept of jacketed rooms where curtained areas within older coolrooms could be held at steady gas compositions. As gas measuring equipment became cheaper store managers were able to maintain atmospheres with greater precision.

Later, in the 1970s, new coolrooms were built from sandwich panels of steel sheet with very efficient foam insulation. These could be sealed very well and as long as an expansion bag was present to cope with changes in atmospheric pressure the required atmosphere could be retained in the cold room.

Improved research facilities assist industry development

Blackwood Experimental Orchard:

The coolstores at the Blackwood Experimental Orchard were built in the early 1950s. The rooms were cooled by re-circulating refrigerated brine which was cooled by a mechanical refrigeration unit running on ammonia gas.

It was here that the early work on controlled atmosphere storage was done using a facility built by W.B. McGlasson. It consisted of individual cabinets made of galvanised steel with flexible transparent fronts. The CO2 generated by the fruit was scrubbed from the atmosphere using water through which the air was circulated. These systems used motor vehicle petrol pumps. Gas composition was titrated using wet chemical methods.

Northfield Research Laboratories:

Initially Tugwell used prefabricated rooms and refrigerated containers at Northfield, but in the early 1970s a state of the art unit was built with panel rooms housed within a larger structure. Various approaches to gas management could be trialled, and gas composition could be measured with infra-red gas analysers.

Improving harvest dates

It was recognised that precise timing of harvest led to a better product for the consumer and more predictable performance in storage. Tugwell and Chvyl used fruit phenological observations and ground colour changes in the fruit to assist growers and packing shed managers to predict maturity and make the best harvest decisions for the major varieties.

The Council for Scientific and Industrial Research produced a colour chart for use when picking apples for export in 1929.

Changing boxes and cartons

There have been considerable changes to the way apples are packed for market. Some of the topics that received attention over the century were:

- Scarcity of wood for box construction caused the switch to cardboard cartons.

- Problems in the use of second hand boxes for interstate trade and local sales.

- The SA apple industry pioneered the use of returnable plastic crates for local marketing.

- Packing patterns and case fill levels to ensure absence of bruising and minimise movement in the boxes (see attached packing pattern guide).

Early hand wrapping and packing apples in bushel wood boxes.

Further reading

- Bain H.D.; (1966) The wirebound box for apples? South Australian Journal of Agriculture Dec 1966

- Tugwell B.L.; (1977) Plastic returnable containers and alternative packaging for the apple industry, SA Department of Agriculture Bulletin 25.77

References

Hawke, E (1912) Apple growing. Journal of Agriculture of South Australia XV1 92-93

Krichauff, F. E. H. W. (1892) Report of the Agricultural Bureau for the year ending June 30th, 1892, p3.

Laffer, G. R. (1913) The Fruit Industry a paper presented to the Blackwood Agricultural Bureau, February 10th, 1913. Journal of Agriculture of South Australia XV1 916-917.

McAlpine, D. (1913) Bitter Pit in Apples. Journal of Agriculture of South Australia 667-672

McGlasson, W. B. (1956) Come common Storage Disorders of Apples and Pears. Journal of the Department of Agriculture South Australia 60, 207-219

Quinn, George. (1912) The Fruit growing industry: its position and prospects. Journal of Agriculture of South Australia XV1 458-465.

Quinn, George (1925) Problems of apple transport. Report of a paper given to the Blackwood Agricultural Bureau on June 9th, 1925. Journal of the Department of Agriculture South Australia XXIX, p88.

Simons, D.H. (19..) Calcium sprays aid control of Bitter Pit.

Steed, J. N. (1969) The future for Jonathans. Journal of the Department of Agriculture South Australia 72 332-337.

Steed, J. N. (1967) Our apple production – ten years above the million. Journal of Agriculture South Australia ……300-308.

Strickland, A. G.(1942) Australian Fresh Fruit in the United Kingdom. Department of Agriculture South Australia Bulletin No 379.

Tugwell, B. L. (1970) Controlled atmosphere storage of apples and pears. South Australian Department of Agriculture Extension Bulletin No 28/70.

Tugwell, B. L. (1997) Evaluation of Storage Performance and Storage systems for new Apple varieties. HRDC Final reports AP123 (1997).

Tugwell, B. L., Chvyl, W. L., and Gillespie K. J. (1989) Handling and Storage of Apples and Pears. Department of Agriculture South Australia Horticulture Notes E/8/89 55pp.

Wicks H. N. (Undated but late 1930s) The Reworking of Orchard Trees. Department of Agriculture South Australia Bulletin No 322..