History of the South East Drainage System – Summary

1. Introduction

The South East Region of South Australia is a highly modified landscape. Broad-scale land clearance and an extensive cross-catchment drainage system have converted what was once a wetland dominated landscape into agricultural production on a vast scale.

There is a long history of drainage in the South East. The first drains in the lower South East commenced in 1863 and the majority were constructed between 1949–1972 largely to remove waterlogging to maintain the region’s productivity and improve accessibility. More recently the lower South East drainage system is also being managed to enhance natural wetlands.

The majority of drains in the upper South East were constructed during the past 20 years as part of the Upper South East Dryland Salinity and Flood Management Program (USE Program). The USE Program was initiated in the early 1990s to address four main elements: drainage, vegetation protection and enhancement, saltland agronomy, and wetland enhancement and management. The USE Program was completed in June 2011.

The South East drainage system (comprising both upper and lower South East drainage system) is unique in that it applies a multi-objective approach to water management at a landscape scale to achieve economic, social and environmental objectives.

Much of the regional economy of the South East has developed over time on the basis of a fully functioning drainage system. The South East drainage system (comprising 2589 kilometres of drains and floodways) is a critical part of the region’s economic and social infrastructure that supports the region’s capacity to undertake economic activity, maintain transport networks and protect highly valued natural environments.

The South East drainage system is operated and managed to enhance environmental and social values, and maximise agricultural productivity through:

- Exporting 250,000 tonnes of salt from the South East region (when rainfall allows).

- Maintaining a 5–10 fold increase in agricultural productivity.

- Facilitating regional economic productivity ($3 Billion/ annum).

- Delivering 26 Billion litres of water to the Coorong South Lagoon, under normal rainfall conditions.

- Providing available environmental flows to 40,000 hectares of connected wetlands in the upper South East.

- Improving the working relationship between government agencies, local councils and key stakeholders.

Drainage in the South East has a long and varied history - both in terms of arguments for and against drainage in general, and certain schemes in particular. The purpose of drains and the management of surface water in the landscape and who should pay has also been a point of contention.

Legislation and administration have also varied over this time. However, there has always been some form of managing authority, and supporting legislation with wide ranging powers to move water as required and enable construction works.

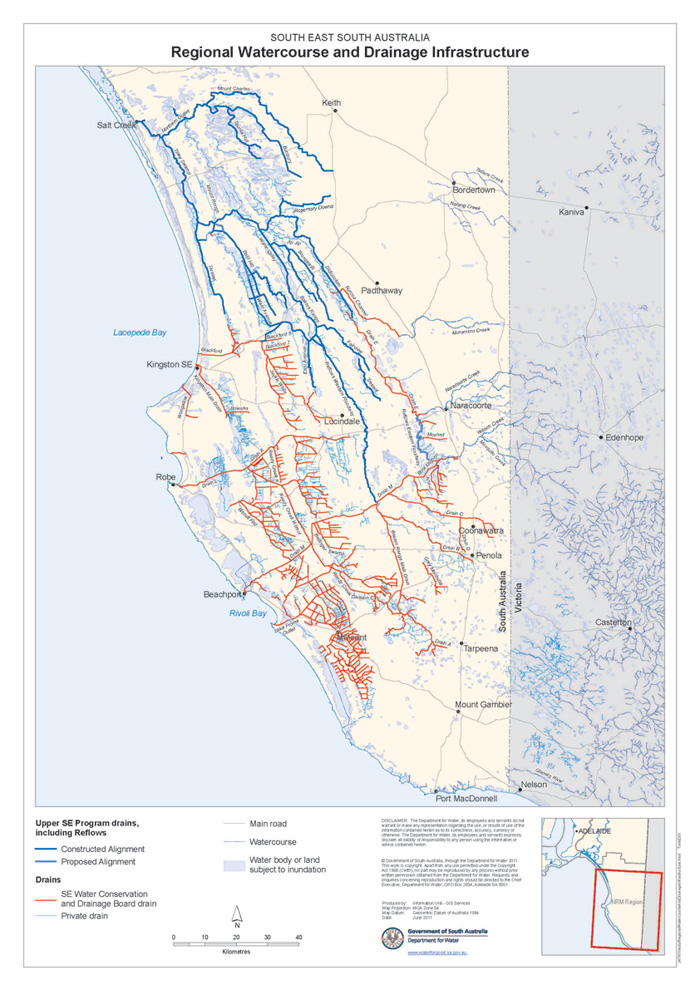

A map of the South East Drainage System is provided in Appendix 1.

A comprehensive history of the South East drainage system is available in two key documents:

- ‘Environmental Impact Study on the Effect of Drainage in the South East of South Australia, 1980, South Eastern Drainage Board [1]

- ‘Upper South East Program – Project Review and Closure Report, 2011, Department for Water [2]

These two reports form the basis of this summary document. Turner and Carter [3] also provide a history of the events and personalities associated with 125 years of drainage in the South East of South Australia.

2. Discussion

2.1 Reasons for drainage

An explanation of the reasons for drainage in the South East must be considered in the context of the regional typology and hydrology, as well as the conditions prior to European settlement. A brief summary is provided in Appendix 2.

Lower South East drainage

From the mid-1840s large pastoral runs were established in the upper and lower South East, and the closer settlement objectives [4] of Government were progressed around Mt Gambier. As the population grew, so did the need for improved communications with Adelaide – both through port facilities, roads and communication services such as regular mail deliveries and general coach services. From 1858 there was a strong push from residents (particularly those in Mt Gambier) for improved road networks.

- From 1958 residents petitioned the Government to spend the revenue raised from the sale of Crown land in the region. This public pressure resulted in the construction of two bridges over Reedy Creek in 1859.

- In 1862, as a result of landholder petition requesting Government to drain the swamps around Port MacDonnell, minor earthworks (ditches and log crossings) were undertaken as part of improvements made for transport access.

In 1863 a complete inspection of the South East region was undertaken by W Hanson (Engineer-In-Chief and architect), W Milne (Commissioner of Public Works) and George Goyder (Surveyor General). This was a significant trip, as it set the vision for the region. Hanson’s primary interest was in draining wetlands to improve access across them during the wet months. Goyder however, had a wider vision and recognised the interests of the South East community. He stated:

The subject is of great importance to the residents in the South-East, and to the colony at large – as a successful prosecution of the work would not only double the area at present available to the stockholder, and place at the disposal of the Crown a large extent of rich agricultural land, but it will also materially aid the general traffic of the country, and enable good roads to be formed at much less cost than must necessarily be expended if the country continues to be liable to inundations from inefficient means to carry off the ordinary winter’s rain. [5]

In 1864, the first drainage works were undertaken – a cutting which separated the inundated Mt Muirhead Flat from Lake Frome and the sea. This is now know as ‘Narrow Neck’ cutting and was the start of the Millicent drainage system.

In 1866 a Parliamentary Select Committee described the reasoning for drainage as:

…there is no better way of facilitating the settlement of the South East District, and of improving it both as pastoral and agricultural country, than by a well devised and carefully carried out scheme of surface drainage. [6]

For many years the key reason for drainage in the lower South East was to increase the productive capacity of the South East region and improve access. Draining land also had secondary benefits such as enabling Crown land to be sold, and land to be made available for post-war soldier settlement. This also facilitated the movement of migrants into the region. In the late 1970s Cabinet directed that no further drainage be undertaken, without prior consideration of the effect of the drainage system on the environment. This may be reflective of the broader movement for Governments to consider environmental impacts prior to undertaking development, as well as an increased awareness of the need for integrated water resources management [7].

Upper South East drainage

Drainage in the upper South East has a more recent history – the majority of drains were constructed over the past 20 years. A combination of persistent and prolonged flooding of low lying lands during rainfall events, and the presence of dryland salinity placed at risk the agricultural productivity of the region. This was as a result of a combination of factors including:

- Land development and vegetation clearance during the 1950s and 1960s.

- Loss of lucerne pastures – as a result of aphid attacks during the 1970s and an inability to replace lucerne with aphid resistant crop varieties.

- Surface flooding and saline groundwater – the regional hydrology is generally slow flowing with flooding of low lying areas, and loss of pasture from such an extensive area contributed significantly to the local recharge of groundwater.

The region as a whole grappled with the dual issues of high saline groundwater coming to the surface through the rising water table and high rainfall events that had the effect of swamping the agricultural area, particularly towards the northern parts of the upper South East where there was no drainage. The large scale of the environmental degradation was a direct threat to the regional economy and the ongoing prosperity of the South East [8].

Landholders were instrumental in driving the development of drains in the upper South East. The 1981 flood first stimulated landholders in the northern part of the upper South East to seek solutions to the problems created by excess water. Many landholders undertook their own drainage works but recognised the need for a coordinated and consolidated approach to surface drainage, and the need for an outlet for landlocked watercourses. At the same time landholders began to recognise the extent of dryland salinity. A number of community groups (including soil conservation boards, landcare groups, and national parks consultative committees) took an interest in developing management solutions. Government groups such as the Bakers Range/Marcollat Watercourse Working Group and Land Resources Management Steering Committee undertook formal investigations. A Upper South East Dryland Salinity and Flood Management Plan Environmental Impact Statement was prepared in 1993 and in June 1995, State Government endorsed the staged implementation of the Upper South East Dryland Salinity and Flood (USEDS&FM) Management Plan. The USEDS&FM Plan outlined an integrated package of solutions to combat rising watertables while taking into account environmental, economic and social concerns [9]. Four key elements of the package were a coordinated drainage scheme, surface water and wetland management, revegetation, and agricultural production and on-farm measures.

2.2 Construction history (LSE and USE)

With the exception of some private works, drainage works have been designed and constructed under the authority of the Government. Seven specific periods of intensive major construction apply within the South East region as outlined in Table 1. Substantial works have been completed under various schemes resulting in 1875 km of drains in the lower South East and 714km of drains and floodways in the upper South East. A detailed history of construction of the drainage system is available in the USE Completion Report [10] and Environmental Impact Study undertaken by the SED Board [11].

2.3 Drainage design

The typography of the South East, which includes a low gradient from South to North, means that shallow drains of less than .5 metre have the potential to have a significant impact on the landscape. There is a strong history of divergent opinions on the design of drains – especially in relation to groundwater and surface water interactions, and depth and width requirements of drains. Cost benefit has always been an overriding consideration in the planning and design of drains [16]. However, compromises have often been made between depth and width of drains, to satisfy landholder concerns. In its 1980 Environmental Impact Study, the South Eastern Drainage Board recognised that in many of the early schemes, farming objectives and the techniques of the day dictated the planning of drains, and designers aimed at achieving these objectives at a reasonable cost. The Board recognised that as knowledge and technology grow, future drains could be designed to achieve a broader range of benefits, not wholly agricultural [17].

Table 1: Major construction periods for the South East drainage system.

| Construction periods/ schemes | Construction | Purpose | Financed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Millicent-Tantanoola System (1864–1883) | 361km (approx) drains 40,000 hectares of land drained, making it suitable for agriculture | Remove water from land. Access and transport. | |

| National Drains (1883–1908) | 310 km (approx) drains constructed | Extension of existing system – extend drainage operations to the north and improve the northerly flowing watercourses. Settlement of land. | Financed by Government |

| Scheme Act Drains (1911–1925) | Sea outlets constructed (Lake George, Drain M outlet). 245km drains constructed east to west – Drains A-E, L-K, M | Drains constructed pursuant to the South-Eastern Drainage Scheme Acts, 1908 and 1910. Essentially to improve east to west drainage. | Half of construction costs borne by landholders (supported by the Scheme Drain enabling Act 1908). |

| Petition Drains (1905–1950) | 170km (approx) drains constructed | Landholders petition Government to undertake certain construction, the cost of which to be borne entirely by landholders. | Cost borne by landholders. However, in the course of construction some petition schemes were absorbed into later schemes. Subsequently some liabilities and charges were discharged for specific ‘petition’ drains [12]. |

| Comprehensive Scheme or Andersons Scheme (1950–1972) | Extension of existing system. Enlarge drains L–K. Construction of Wilmot drain and other ‘trunk drains. Construction of Eastern Division drains (220km) | Remove surplus water from flats. | Landholders were to pay an annual ‘betterment’ rate (a portion on the basis of the increase in the fee simple value of land, a result of drains and drainage works [13]. |

| Upper South East Scheme (1990–2011) | 714km of drains and floodways | Dryland salinity, flood mitigation, water for environmental purposes | Phase 2 – landholders contributed $6 million (25%). State and Australian Government funded 37.5% ($9 million) each [14]. Phase 3 – landholders contributed $11 million. State and Australian Government funded $19.15 million each [15]. |

| Private drainage works (ongoing) | Numerous small private drains, primarily in the lower South East. Some in the upper South East. | Primarily to remove water from land. | Landholder cost. |

During development of the USEDS FM Plan there was considerable debate about the appropriate depth of drains required to control salinisation. Drainage trials were undertaken to evaluate the effect of various drains - groundwater drains were considered to be those greater than 2 metres deep and those up to 2 metres deep, major surface water drains. From the trials, it was found that the best value for money were the 2 metre deep drains, which had a significant effect on groundwater as well as removal of surface water. Due to a number of factors including soil conditions, topography, potential environmental impacts and the cost of excessively deep drainage, only drains (up to a nominal depth of 2 metres) have been constructed in the upper South East since 1998. In areas of higher ground eg the Northern Outlet Drain, deep cuts have been required to maintain flows. While historically, drains up to 2 metres deep were considered shallow, many members of the community now considers “deep” drains those greater than 0.5 metres deep.

2.4. History of drainage administration in the South East and legislation

The history of drainage administration has had significant impacts upon the development of the regional structure and economy. It has been actively managed, at various times, under State Government direction but has also been managed via several District Drainage Boards that inevitably became Local Government District Councils for these areas with responsibility for drainage works.

In the early stages of settlement, the South East drainage works were a by-product of the public works carried out by Government – particularly road and railway works. As drains increased in importance in the landscape, it was necessary to establish an authority charged with their construction, control and maintenance. Originally, works were carried out under authority from the Commissioner of Public Works. These works were transferred to the Survey Branch of the Crown Lands Department. In 1875 the South Eastern Drainage Act 1875 was introduced and passed by Parliament. The preamble to this Act stated:

‘Whereas certain works have been constructed and are in course of construction in the South-Eastern district of South Australia, for the drainage and reclamation of land therein, and it is intended to extend such works for drainage and reclamation of other lands, and it is expedient to make provision for the maintenance and construction of the said works respectively, and for other purposes connected therewith.’

South East Drainage Boards were established on a district by district basis, and in 1895 Drainage Boards became District Councils, and the members became Councillors from that date [18]. From 1908 to 1926 responsibility for the control of works and management of the drainage system changed hands a number of times, and numerous amendments were made to the legislation.

- In 1908 the control of works was removed from the District Councils and put under the Commissioner of Public Works. A new Assessment Board was created and a Drainage Management Board was appointed.

- In 1917 the Drainage Management Board was abolished and the care, control and management of the drains resided with the Assessment Board.

- In 1926, following the passage of the South East Drainage Act 1926 the Irrigation and Drainage Commission had care, control and management of the drains.

- In 1931 the South Eastern Drainage Board was set up for the care, control and management of the drains.

- Legislative amendments during the 1940s and 1950s empowered the South Eastern Drainage Board to progress construction regarding the Comprehensive Scheme or Andersons Scheme [1950-1972]. Further amendments were made in the 1970s relating to landholder liabilities on Scheme and Petition drains, and tied the revenue directly relative to expenditure on the care, control and management of drains.

- In 1992, the South Eastern Water Conservation and Drainage Act 1992 repealed the South-Eastern Drainage Act 1931 and the Tatiara Drainage Trust Act 1949.

- In 2002, the Upper South East Dryland Salinity and Flood Management Act 2002 was passed by Parliament, providing specific powers for the construction of the upper South East drainage system. This Act removed the entire upper South East Project Area from the administrative control of the South Eastern Water Conservation and Drainage (SEWCD) Board. On expiry of the USE Act on 19 December 2012, all interests in the upper South East vested to the SEWCD Board, who is now responsible for operating, managing and maintaining the total South East drainage system on behalf of the Minister.

Since its inception in the 1870s the successive authorities have contributed to improving the productivity of the region, and more recently to protect and manage significant water dependant ecosystems of the region. The Drainage Board has continued to evolve as the needs and expectations of the regions have evolved. Initially the Drainage Board was concerned primarily with flooding and productivity. Today it manages a complex drainage system to meet multiple objectives including flooding, productivity, and environmental, social and recreational objectives.

The key legislation over time is outlined in Appendix 3.

2.5 Landholder involvement participation

Landholder involvement and participation has been a key element throughout the history of the South East drainage system. Much of the original drainage works in the lower South East were undertaken as a result of public demand for improved transport networks. Petition Drains [1905–1950] (those drains constructed by the Crown, on request of the landholder) enabled the authorities to be considerate of and responsive to landholder needs. Landholders were also engaged during various Parliamentary enquiries regarding proposed works. The 1971 Act altered the constitution of the Board to 4 members – 2 of those elected by ratepayers and to be landholders of land in the South East. The ensuing Acts have all recognised the relevance of local representation and involvement in Board activities. The current SEWCD Act provides for 8 members in total. Three of these are landholder representatives – one each from the North, South and Central zones, four are members nominated by the Minister and appointed by the Governor, and one member is nominated by the Local Government Association.

2.6. Drainage rates and cost recovery for construction

Government has had a close connection with drainage construction and finance from the beginning [19]. Since inception (under the South-Eastern Drainage Act 1875 and various iterations) the Drainage Board or relevant authorities has been able to apply drainage rates to landholders for the purposes of cleaning, repairing and maintaining drains. The application of these drainage rates has at times been divisive.

As drainage was extended for the purposes of reclamation and settlement, Government revenue (through sale of land), and for extending farming operations, Government had to find methods and means for cost recovery of construction. Many early schemes were partially funded by landholders (see Table 1) – Government would often pay the construction costs upfront (following Parliamentary approval) and the relevant authority (either the Drainage Board, Drainage Assessment Board, Minister, Council) would apportion the cost of construction of the drains amongst landholders whose lands benefited by the drains. The SEDM Board summarised the various approaches as a ‘complicated process of financing proposed works’ [20]. This is reflected in the numerous Royal Commission held in the early 1900s and numerous amendments to legislation to address landholder liabilities.

As a result of, and following the Royal Commission of 1923, a series of Acts were passed in attempt to satisfy the landholders concerning their liability under the Scheme Drains [21]

In 1958 the Parliamentary Committee on Land Settlement recommended that a policy be formulated to enable the South Eastern Drainage Board to impose a betterment rate on landholders as the drainage scheme progresses. In 1968 Cabinet approved the formation of a Committee to investigate and report upon the financial sections of the South Eastern Drainage Act 1931–1959 [22]. The primary cause of concern lay in the inequality of the various rating methods used:

- Old Scheme Drains – landholder contributions were based on maintenance rate and capital contribution

- Petition Drains – landholders were levied on capital contributions

- Western Division – landholders were levied based on maintenance rate and capital contributions

Subsequently, in 1971, the South Eastern Drainage Act Amendment Act No 12 of 1971 was assented to. This abolished all ratings methods in operation prior to 30 June 1972 and a new system based on unimproved land values came into force on 1 July 1972 [23]. However, following unsuccessful attempts to raise a levy/ drainage rates from landholders, the State Government took over total financial responsibility for the South East drainage system in 1980. Since that time the Government has provided base funding to the Drainage Board. However, this has been insufficient to meet ongoing maintenance and management activities and over time has resulted in a backlog of works.

In 1980, further legislative amendments were made to reintroduce petition drains, and provide that the authority (either Drainage Board or Council), within 3 years after the completion of drainage works to make an apportionment of costs that the Minister determines must be paid, between the landholders benefited by the drains or drainage works. These provisions continued until the SEWCD Act came into operation in 1992.

In 1995 amendments to the SEWCD Act were introduced and passed, allowing the Drainage Board to collect a levy from landholders in the upper South East to be applied towards the cost of carrying out works involved in the Upper South East Project. This enabled the collection of the agreed community share of 25% ($6 million) for Phase 2 of the USE Program. The levy was applied to landholders at differing rates according to where land is situated. There were four main conditions used to estimate the determination of the final levies – direct benefit from scheme, indirect benefit from scheme, contribution to the problem via ground water, contribution to the problem via surface water, social and moral obligation to overcome a regional problem. Following consultation with landholders, the levy was broken down into four zones. Zones A and B were deemed to receive the most benefit from the drainage system, zones C and D were identified as ‘contributing’ zones to the groundwater and surface water drivers of the salinity issues. This levy continued to be collected until 2004–05.

In 2002, the Upper South East Dryland Salinity and Flood Management Act 2002 (USE Act) was enacted and included specific levy provisions to enable the Minister to raise a levy for the purposes of works or activities associated with the Upper South East Project ie construction only. This enabled the Minister to collect the agreed community share of 22.5% ($11 million) for Phase 3 of the Upper South East Program. A similar approach was applied to the levy raised under the USE Act - three zones were established. As at 31 December 2012, 99.15% of landholders (1392) have either fully paid or offset their levy amount.

The levies raised for the USE Program were for constructions purposes only, not for ongoing management and maintenance of the drainage system.

2.7. Asset management and maintenance

The South East drainage system has a combined total of infrastructure assets worth $237.5 million (replacement value). The accepted industry standard annual expenditure for management of assets of this type is 3% per year, equating to $7.125 million. The State currently allocates $2.1 million (+ indexation) per annum (recurrent and capital) to the SEWCD Board to operate, manage and maintain the South East drainage system. Over the past 2 years, the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) has provided additional funds - $5.4 million in 2011-12 and $5.558 in 2012-13 to the South East Drainage and Wetland Management Program. Of this approximately $3 million, per year was granted to the SEWCD Board to address a serious deterioration of assets and backlog of maintenance issues in the lower South East, with the remaining funding supporting completion of the Upper South East Program.

The Government anticipates that a levy will be raised in the future, through a dedicated South East drainage levy, as is currently proposed by the South East Drainage System Operation and Management (SEDSOM) Bill. The SEDSOM Bill was introduced into Parliament on 31 October 2012.

Additionally, the entire South East drainage system is located upon land assets where the SEWCD Board holds a variety of different interests. This adds an additional level of complexity for rights to access and maintain all relevant infrastructure for which the Board has responsibility.

2.8. Present and future management

The South East makes an important contribution to the State’s Gross Domestic Product (in the order of $3 billion GDP) largely through primary production, energy resources and tourism. Much of the regional economy of the South East has developed over time on the basis of a fully functioning drainage infrastructure system. As a total system the South East drainage system and associated infrastructure is operated and managed to perform a number of vital functions including:

- Regional arterial flood and salinity management services – managing water to minimise flooding on agricultural lands and to enhance productivity of salt affected land.

- Protection and enhancement of wetland and watercourse ecological values – providing environmental flows to key wetlands, including the Coorong South Lagoon.

- Local and regional access - maintaining road bridge crossings and occupational crossings (bridges and culverts that provide access to and across private land to allow continued access for landowners and SEWCD Board staff).

- Regional amenity – managing water to facilitate recreational activities.

These functions reflect the dynamic nature of operating and managing the South East drainage system to meet multiple and at time competing objectives. Effective management of water in the drainage system is critical to the sustainable use of water in the South East and requires contemporary legislation, robust strategic and operational policies, robust asset management practices and corresponding funding.

3. Appendices

3.1 Appendix 1 – South East Drainage System Map

3.2 Appendix 2 – South East Regional Hydrology and Topography, Land use history

A. Topography

The South East region has many unique landforms and distinctive natural characteristics that have originated from a long, complex geological history. The region is characterised by a series of shallow parallel elevated ranges historic sand dunes. Each of the inter-dunal range plains has a slight gradient decline [east to west] representative of a slow receding shoreline. The plains are further impacted by another slight decline from South to North caused by a tilting of the plain from volcanic activity in the Lower South East. These plains can be inundated over winter and host a variety of internationally recognised wetland systems including the Ramsar listed Bool and Hacks Lagoons and part of the Coorong and Lower Lakes wetlands and 12 additional wetland complexes listed in the Directory of Important Wetlands in Australia (ANCA 1996). The region also hosts an extensive network of limestone sinkholes and caves, which include the World Heritage, listed Naracoorte Caves [24].

B. Hydrology

The South East region currently supports a relatively high and reliable rainfall ranging from 800 mm annual average at Kalangadoo to 500 mm at Salt Creek. Approximately 80% of this rainfall occurs in the winter months between May and October. A combination of soil type (self-mulching grey clays and sand over clay), geology (soils often occur over limestone and/or calcrete) combined with a shallow regional unconfined watertable, means that saturation capacity can be attained relatively early in the season. Any rainfall after saturation is generally expressed as surface water run-off. There are also occasions where rainfall intensity is greater than the capacity for permeation into the soil profile. Generally, this results in surface run-off traversing the landscape and pooling in the lowest lying part of the landscape between ranges.

Maps of the historical surface water movement and pre-drainage water conditions are available in SEDB‘s Environmental Impact Study [25].

C. Biodiversity

Prior to European settlement the South East of South Australia comprised a mosaic of both freshwater and saline wetlands running from the South Australian-Victorian border through to the Coorong (DEH, 2009) [26]. Today the SE Region of South Australia is a highly modified landscape. Broad-scale land clearing and an extensive drainage network have converted what was once a wetland dominated landscape to agricultural production on a vast scale [27].

Although only 13 per cent native vegetation cover remains, the region has diverse flora and fauna and diverse habitats that include healthy woodlands and forests, grassy woodlands, dry heathlands and mallee, scattered trees, open water swamps and wetlands and rising springs. The coastline is largely undeveloped and has distinctive features which include coastal lakes and limestone cliffs. Significant areas of the coastline are protected areas under the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972, with coastal scenery and beaches a major attraction of the region. The marine environment is mostly high energy and is significant for its high biodiversity and high productivity [28].

Many nationally threatened species are represented only in the South East region of South Australia and survive in isolated pockets of suitable habitat. The South East drainage system has an important role in providing water to key environmental assets – both on public and private lands. Some key endangered species include Yarra Pygmy Perch, Southern Bell Frog, migratory waders eg Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, Red-necked Stint, and Common Greenshank, and Orange-bellied Parrot.

D. People

Prior to European settlement, Tanganekald, Meintangk, Bunganditj, Ngarkat and Potaruwutj Aboriginal people lived in the SE NRM Region. The entire south-east coast is important as an Aboriginal heritage area [29]. All landscapes in the region are extremely important to Aboriginal people today, just as they were prior to European settlement. Non-indigenous settlement in the South East followed the exploration for pastoral land with the importance of the Coorong as a corridor to assist movement and communication through the settled areas.

E. Land use change

Agricultural production (comprising of wheat and other grain crops) required a considerable period of lead time in which to clear and develop the landscape for that use, whereas pastoral production (sheep and cattle grazing) required little or no clearance or development and provided for immediate returns for meat, wool and hides.

Land use change following European settlement was very rapid. The first Europeans used the open woodland vegetation for grazing of sheep and cattle with some attempts at cropping undertaken. However, with approximately 40% of the region regularly inundated, much of what is now productive agricultural land was then often rendered extremely difficult to farm effectively. To overcome problems associated with inundation, the landscape has been extensively drained with the first drains installed in the Millicent area in the 1880s. The second major change to land use occurred as a result of the mechanisation of native vegetation clearance following the Second World War (WWII), with large areas being cleared in the mid and upper South East [30].

Since the 1980s land use change can be characterised as:

- Intensification of agriculture away from extensive grazing to intensive irrigation (80,000 ha);

- Intensified grazing and a movement to cropping;

- Conversion of agricultural land to plantation forestry.

3.3 Appendix 3 – Key legislation

| Title | Year |

|---|---|

| Waste Lands 6 Vic 1842 No. 8 | 1842 |

| Crown Lands 10 Vic., 1846, No. 11 | 1846 |

| South-Eastern Drainage Act 1875 (No 21 of 38 and 39 Vic, 1875) | 1875 |

| S.E. Drainage 58 and 59 Vic., 1895, No. 629 | 1895 |

| The South-Eastern Drainage Amendment Act 1900 (No 737 of 63 and 64 Vic, 1900) | 1900 |

| Irrigation and Reclaimed Lands Act 1908 | 1908 |

| The South-Eastern Drainage Act Amendment Act 1908 (No 962 of 1908) | 1908 |

| The South-Eastern Drainage Scheme Act (963 of 1908) | 1908 |

| The South-Eastern Drainage Act Amendment Act (No 989 of 1909) | 1909 |

| The South-Eastern Drainage Scheme Act 1908 (No 1027 of 1910) | 1910 |

| South-Eastern Drainage Act (Further Amendment Act (No 1295 of 1917) | 1917 |

| South-Eastern Drainage Act Further Amendment Act, 1919 | 1919 |

| South-Eastern Drainage Act :Further Amendment Act, 1921(No 1481) | 1921 |

| South-Eastern Drainage Act (No 1781 of 1926) | 1926 |

| South-Eastern Drainage Act Amendment Act (No 1817 of 1927) | 1927 |

| South-Eastern Drainage Act (No 2000 of 1931) | 1931 |

| South-Eastern Drainage Act 1931, No. 2062 | 1931 |

| South-Eastern Drainage Act Amendment Act 1933, No. 2126 | 1933 |

| South-Eastern Drainage Act Amendment Act 1935, No. 2219 | 1935 |

| South-Eastern Drainage Act (No 25 of 1947) | 1947 |

| South-Eastern Drainage Act Amendment Act (No 34 of 1948) | 1948 |

| South-Eastern Drainage Act Amendment Act (No 25 of 1959) | 1959 |

| South-Eastern Drainage Act Amendment Act (No 91 of 1969) | 1969 |

| South-Eastern Drainage Act Amendment Act (No 112 of 1971) | 1971 |

| South-Eastern Drainage Act Amendment Act (No 152 of 1972) | 1972 |

| South-Eastern Drainage Act Amendment Act (No 11 of 1974) | 1974 |

| Eight Mile Creek Settlement (Drainage Maintenance) Act Amendment Act, 1980 No. 42 of 1977 | 1977 |

| Eight Mile Creek Settlement (Drainage Maintenance) Act Repeal Act, 1980 No. 40 of 1980 | 1980 |

| South-Eastern Drainage Act Amendment Act (No 42 of 1980) | 1980 |

| South-Eastern Drainage Act Amendment Act (No2) 1980 No. 112 of 1980 | 1980 |

| South-Eastern Drainage Act Amendment Act No. 8 of 1983 | 1983 |

| South-Eastern Drainage Act Amendment Act No. 38 of 1985 | 1985 |

| South Eastern Water Conservation and Drainage Act (No 16 of 1992) | 1992 |

| South Eastern Water Conservation and Drainage (Miscellaneous) Amendment Act (No 104 of 1995) | 1995 |

| South Eastern Water Conservation and Drainage (Contributions) Amendment Act (No 102 of 1996) | 1996 |

| Upper South East Dryland Salinity and Flood Management Act 2002 | 2002 |

Footnotes

[1] South Eastern Drainage Board (SEDB), Environmental Impact Study on the Effect of Drainage in the South East of South Australia (South Eastern Drainage Board Publishing, 1980)

[2] Department for Water (DFW), Upper South East Program – Project Review and Closure Report, (Department for Water, 2011)

[3] Turner and Carter, Down the Drain – The Story of Events and Personalities Associated with 125 years of Drainage in the South-East of South Australia, (South-Eastern Drainage Board, 1989)

[4]see Closer Settlement Act 1897

[5] in Turner and Carter, Down the Drain – The Story of Events and Personalities Associated with 125 years of Drainage in the South-East of South Australia, (South-Eastern Drainage Board, 1989), p8

[6] SEDB, op. cit. p154

[7] DWLBC, The History of Water Resources Management in South Australia 1970-2004, (DWLBC, 2007) – identifies the water issues facing South Australia at the time, and the need for Government to shift its policies in relation to water management.

[8] DFW, op. cit. p11

[9] DFW, op. cit. p13

[10] DFW, op. cit. – provides a detailed list of drains constructed as part of the Upper South East Program (1990–2011), pp19–20, p30, p35.

[11] SEDB, op. cit. – see Appendix XIII, p125

[12] South-Eastern Drainage Act (Further Amendment Act (No 1295 of 1917)

[13] South-Eastern Drainage Act Amendment Act (No 34 of 1948)

[14] Raised under the South Eastern Water Conservation and Drainage Act 1992

[15] Raised under the Upper South East Dryland Salinity and Flood Management Act 2002

[16] SEDB, op. cit. p73

[17] SEDB, op. cit., p73

[18] SEDB, op. cit., p39

[19] SEDB, op. cit., p35

[20] SEDB, op. cit., p35

[22] SEDB, op. cit., p123

[23] SEDB, op. cit., p123

[24] As described in the South East Flows Restoration Project – Phase 2 Business Case (12 March 2013)

[25] SEDMB, op. cit. – see Map 2 and Map 3

[26] As described in the South East Regional NRM Plan – Part 1 (SE NRM Board, 2011), p37

[27]ibid.

[28] As described in the South East Flows Restoration Project – Phase 2 Business Case (12 March 2013)

[29] South East Regional NRM Plan – Part 1 (SE NRM Board, 2011)

[30] As described in the South East Regional NRM Plan – Part 1 (SE NRM Board, 2011)