Help is at hand: 1971–2000

This article is the sixth in this series about introduced pest animals and weeds in South Australia, summarising the events from 1971 to 2000.

In this period, the value of research into pest animals and weeds was recognised and increased. Research was integrated into control programs and a structure was put in place to disseminate those scientifically based control programs to primary producers and the community. Legislation was rationalised and consolidated under one Minister and eventually just two Acts.

In previous articles of this series, information was divided into either pest animals or weeds, including the legislation and local boards. In this article there is an additional heading about the combined local boards and central body, which came about because of integrating animal and plant control legislation.

Agricultural events

Weather conditions, including drought, continued to influence agricultural production throughout this period with fluctuations in livestock and crop returns which continued to also impact pest animal and weed infestations. South Australian average temperatures have been rising steadily since the 1970s, with a clear decline in average rainfall since that time. [1]

The 1982 to 1983 drought was one of Australia’s most severe in the 20th century. This drought peaked with the devastating Ash Wednesday bushfires but relief came with the large March rain event. Beginning in 1997 (for 12 years) much of southern Australia experienced a prolonged drought period which severely affected the Murray–Darling Basin and virtually all the southern cropping zones. [2]

During this period there were many changes in farming systems. As an example, cereal growers who had adopted ‘ley farming’ systems were moving into minimum tillage and continuous cropping by 1990s. With new grain varieties, better marketing characteristics, and other improvements, the cereal industries increased their yield by over 2% per annum during the period 1978–1998. However, the numbers of farmers progressively declined so that by 2000 only 3-4% of the population was directly engaged in agriculture, even though the production of agricultural commodities was generally higher than ever. At the same time farmers became more conscious of the importance of conservation of the natural resources upon which their enterprises depend, beginning with land-use changes initiated through the landcare movement in 1990. [3]

As related in Part 5 – science to the rescue: 1921 to 1970, a Parliamentary Standing Committee on Land Settlement was appointed in 1945, and this continued to operate until 1982. However, no other relevant Parliamentary committees were established until 1998 with four being appointed in quick succession:

| Date | Parliamentary committee |

|---|---|

03/06/1998 | Select Committee on the Pastoral Land Management and Conservation (Board Procedures, Rent, Etc.) Amendment Bill and Coverage of the Principal Act |

10/12/1998 | Select Committee on Water Allocations in the South East |

25/11/1998 | Select Committee on Wild Dog Issues in South Australia |

18/11/1999 | Select Committee on the Murray River |

The oil embargo of 1973 had a serious impact on agricultural production. The price of oil quadrupled and inflation jumped from 6.5 per cent p.a. in 1972 to 15.3 per cent p.a. in 1975. Unemployment doubled from 2.6 to 4.9 per cent. [4]

During the late 19th and for the first half of the 20th Century, the railways had traditionally been used to transport agricultural produce. Country rail services were reduced with agricultural produce increasingly transported by road with most country lines closing by 1990. A boost to priority agricultural exports was provided in 1982 when international air services commenced from Adelaide Airport. [5] During this period the State’s population rose from 1,173,000 in 1971 to 1,500,000 by 2000.

These significant changes had a profound effect on the agriculture sector and as such on the control of pest animals and weeds.

Pest animal control

The control of pest animals continued to be difficult for those on the land during the period from 1971 to 2000. However, help was at hand with scientifically backed control programs being developed and readily available. Legislation was rationalised and remained stable in comparison from the previous period. There was a significant reduction in the number of principal Acts relating to pest animal control in South Australia during this period compared to previous periods and these are highlighted throughout the text. In addition, pest animal control for this period is governed by a policy direction carefully set and implemented by Government.

Up until 1975 the word “vermin” was in general use for what we now refer to as pest animals. From 1975 to 1987 the term “vertebrate pests” was used and then until 2000 “proclaimed animals” was the terminology used. Throughout the text below, these terms have been used for the relevant times. Again, this article just concentrates on those pest animals that were introduced to Australia, including the dingo which arrived in Australia from South East Asia about 3,500 years ago.

Legislation overview

Legislation overview

The Vermin Act and the Wild Dogs Act were in force at the beginning of this period and both generally provided for the control of pest animals. Although amended a number of times since they came into operation in 1931, they were outmoded and a new approach was needed in changing times. Focus turned to providing landowners with the tools to control pest animals on their land, particularly given that owners had the responsibility to do so.

In 1975, Parliament passed new legislation as a modern and more effective legislative expression for that purpose, the Vertebrate Pests Act. This new legislation continued to require the landowner to control vertebrate pests on that land thereby reducing the loss to agriculture and damage to the environment. The Act was designed to achieve persistence and cooperative effort between State Government, local government and landowners for the control of vertebrate pests. [6]

For the first time, a Statewide, dedicated body called the Vertebrate Pests Control Authority, was established with a primary function of ensuring that landowners discharged the above obligation on their land. In addition, the Authority had a responsibility to conduct research into the control of vertebrate pests, to record the distribution of vertebrate pests within the State and to advise on the development and implementation of programs for the control of vertebrate pests. The Authority reported directly to the Minister and consisted of initially the head of the Department of Lands as the Chairman and six other persons of whom not less than three were primary producers. The Chairman was later changed to be a person in an office (in the Public Service) determined by the Governor. The Authority had specialist staff (initially 13) for assisting the Authority carry out its functions.

At the local level, individual councils could continue to administer the new Act in their areas or, with adjoining councils, agree to establish a board comprised of persons representative of each council to enable costs to be shared. Councils or boards carried out a limited role in enforcement, ensured land was inspected to determine whether vertebrate pests were being controlled, and kept records of vertebrate pests within their area. The Authority was tasked with the larger role in enforcement within council/board areas, as under the previous legislation there had been issues with locals carrying out enforcement on locals. The legislation also provided for adjoining landowners to contribute towards the cost of rabbit-proof or dog-proof fencing and for the supply and use of poisons for vertebrate pest control. [7]

The Vertebrate Pests Act was framed on possible future needs to include additional animal species. The Vermin Act had dealt only with pests associated with agriculture but it was recognised that pests other than those of agriculture might need to be proclaimed if necessary. National park and forestry authorities, for instance, were looking to vermin control authorities for answers to problems associated with feral goats, feral cats, native rodents and wallabies etc. while veterinarians were concerned at the lack of knowledge of control measures against many wild species which could act as hosts of exotic diseases. In addition, there was the ability to gather information about species which might need to be acted on later. [8]

This new Act introduced control obligations additional to a landowners responsibility to control vermin on his/her land as provided for under the Vermin Act. These new provisions included prohibitions on the keeping of certain (now termed) vertebrate pests, selling vertebrate pests, releasing vertebrate pests into the wild and transporting vertebrate pests to off-shore islands.

Once established, the Authority supported councils with the establishment of boards and commenced research into pest species and the development of control programs. The species determined to be pests under the Act were the rabbit, dingo, fox and hare, with the latter only applicable on every island within the State. Later, in May 1981, hamsters and gerbils were added as those species were considered to be possible sources of rabies and meningitis with the potential, if established, of becoming serious pests to grain crops and pastures. [9] Research projects initially commenced on rabbits, feral goats and the use of 1080 poison in baits. Later, research was initiated on dingoes and bird damage to crops.

Research on the impact of 1080 poison on non-target species was an important project to ensure the continued availability of this important poison for dingo and rabbit control and the development of a single policy on its use. [10] Initially, six non-target species were identified as susceptible [11] with the project eventually concluding that some off-target species were at a potential risk of poisoning and control programs were amended to reduce this risk.

A further change to the Act was made in 1977 to enable the transfer of the administration of the Vertebrate Pests Act to the Minister of Agriculture and the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries. [12] This occurred in July 1977 ending a 125-year association with Department of Lands.[13] This change simplified the setting up of a single control authority for both animals and plants under one piece of legislation, a proposal that originated at this time took 10 years to come to fruition (see further information below under the heading Combined Government Support Structures for Pest Animals and Weeds).

When this combined legislation, the Animal and Plant Control (Agricultural Protection and Other Purposes) Act 1986, came into operation in 1987, the provisions relating to the now termed “proclaimed animal” control at the local level changed little. Possession of a proclaimed animal and the requirement for a landowner to notify the authorities if certain proclaimed animals were on his/her land were added. At the State level, the new Act enlarged obligations to control the entry, movement and keeping of all vertebrate species except fish and protected native animals. This was to give effect to the Australia-wide agreement for a uniform approach to the control of exotic species. A classification system was also adopted so that, for the first time, feral animals could be proclaimed as pests rather than each species being specifically included by name in the Act . [14] This system was based on an individual species’ “pest potential”.

The initial proclamation of animals in 1987 [15] resulted in the following number of species (528) rated against their pest potential as follows:

Class | Pest potential | No. of species proclaimed |

|---|---|---|

Class 1 | Animals considered to have a major pest potential with entry and keeping generally prohibited. | All animals not native to Australia and not already listed. |

Class 2 | Animals with high pest potential and may be introduced and kept only in registered high security collections. | 209 |

Class 3a | Animals for registered zoological collections for public exhibition. | 50 |

Class 3b | Animals kept for private purposes. | 18 |

Class 4 | Animals recognised as domestic or farm animals or animals having extremely low pest potential. | 242 |

Classes 5 to 8 | Animals recognised or potential pest animals being widespread in the State. | 9 |

The revised legislation provided for the control of many more species of animals than previously, most of which were confined to zoos. Responsibilities of control boards were mainly confined to those animals traditionally regarded as vertebrate pests. There were only four species already occurring widespread in the State that landowners were required to control on their land. Additionally, restrictions were placed on the sale and deliberate release into the wild of certain proclaimed species. As with the previous Act, exemptions could be applied. Again, the requirement for a landowner to control certain pest species on their land was maintained. [16]

During the period from 1987 to 2000 two species were removed from proclamation and seven were added.

Vertebrate pests control boards

The Vertebrate Pests Act provided for a council to enforce the requirement for a landowner to control vertebrate pests upon his/her land, cause inspections to be made of land to determine whether vertebrate pests were being controlled and keep records of vertebrate pests. As stated, contiguous councils could seek a proclamation by the Governor to establish a board covering the area of the councils to carry out these functions. How a board was constituted, its business conducted, membership and finances were all specified in the proclamation.

Immediately the Vertebrate Pests Act came into operation, several councils expressed interest in forming boards with other councils to carry out the requirements of the Act. As the Pest Plants Commission had experience in liaising with local government, the Vertebrate Pests Control Authority met with the Commission to discuss the establishment of vertebrate pests control boards. [17] Progress was slow but steady and 11 vertebrate pests control boards were established by 1981. [18] Three or four boards were formed each year so that by 1986 there were 26 multi-council boards with another in the process of forming. These 26 boards were operating congruently with pest plant control boards throughout the State. [19]

The members and staff of these boards were supported by staff from the Authority. Advice on administration, control programs and the latest research was provided, and the boards were well backed in the enforcement role. Staff from the Authority attended each board meeting whenever possible to reinforce this support.

Pest animal fences

In 1972 a new section of dog fence was completed along the realigned boundary between Mulgaria and Stuarts Creek stations (north east from Roxby Downs) thereby moving the fence away from the sand drift and salt damage prone area across the top of Lake Torrens. This resulted in 66 miles (106 km) of new fence but only added a further five miles (8 km) to its overall distance and enclosed a 491 square miles (1,194 km2). [20]

During 1974-75 the Dog Fence Act was amended to change to metric and to establish local dog fence boards in areas inside and adjoining the fence for the purpose of defraying the cost of its maintenance. These local board areas were previously constituted as vermin fenced districts. In addition, there was a revision of rateable land to only include grazing land except for mixed farming areas on the Far West Coast and to allow the location of the fence to be more easily altered.

The fence had been damaged in a number of areas due to floods and bushfires. [21] In early 1975, widespread bushfires in the north-west of the State severely damaged the western portions of the fence. An estimated 147 miles (236 km) of fence were totally destroyed and 1,730 posts burnt. The intense heat also ruined lengthy sections of the wire. [22]

Dog fence amendments

Dog fence amendments

An amendment to the Dog Fence Act in 1978 provided for the payment and recovery of rates being brought into line with the corresponding provisions in the Vertebrate Pests Act. As rates were imposed under both Acts on the same lands, this amendment enabled the rates to be notified and recovered jointly, thereby reducing administrative costs. [23]

In 1979 the Fence was shortened on the Far West Coast by the exclusion of the Nullarbor and White Well sections. This new alignment followed the west boundary of the Fowlers Bay Local Dog Fence Board. Coupled with this re-siting and the realignment of the Eyre Highway through the Yalata Aboriginal Lands, these moves put the fence on its current (2023) alignment. [24] Wombats were a serious problem to the integrity of the fence on the Far West Coast. It was estimated that about 20,000 wombats lived along 124 km of the Fowlers Bay Fence. [25]

The 1980s involved four amendments to the Act. The 1982 amendment increased the maintenance subsidy, the Government subsidy, the rate charged and the payments made to fence owners. A total of $90,000 per annum would be collected. [26] Two years later a further amendment resulted from lengthy negotiations between a group of fence owners and their immediate cattle lessee neighbours regarding the maintenance of that part of the dog fence that was their common boundary. The cattle lessees had not previously contributed to the maintenance of the fence but were now willing to do so. The amendment allowed for the cattle lessees to be rated so as to contribute a share. This would affect seven cattle lessees who occupied land abutting the outside of the dog fence for an approximate distance of 900 kms. [27]

Amendments in 1986 and again in 1989 were aimed at rationalising the membership of the Dog Fence Board to reflect contemporary needs and updating the nominating bodies. Another 1986 amendment provided for the Board and the local dog fence boards to borrow funds with the approval of the State Treasurer. [28] During the 1980s much of the Parakylia Fence (north east of Ceduna) was protected by a parallel solar-energised, six-plain wire electrified fence principally to deter kangaroos. A major fence deviation made use of electrification to erect a new 80 km fence. This was mainly through what was then unallocated Crown land (now the Pureba Conservation Park) from the north-east corner of the Murat Bay Dog Fence to the southern extremity of the Lake Everard Fence. The work was to protect cropping areas and one grazing license. [29]

In 1989, the Dog Fence Board decided it would enlarge the traditional grazing oriented rating base. The wider rating base was to include every property inside the fence that had an area greater than 10 km2. [30] In 1991, a policy was introduced that provided a fence owner with one metre of materials for every metre he or she purchased. Later, a policy was introduced that provided for payment by the board for all materials used to repair the fence where it had been damaged or destroyed by natural disasters, like flood or bushfire. Later in 1995 and into 1996, the board was to extend its assistance to fence owners further by purchasing fencing materials on their behalf to prevent delays with procurement and delivery of materials in remote areas. The policy coordinated purchases and also made possible some economies of scale. [31]

Map showing the location of the Dog Fence (white line).

Image: PIRSA

Electric fences

In 1995 there were amendments to the Act to redefine 'dog proof fence' to allow the introduction of electric fences which could be a cost-effective alternative to netting in many areas. This provided greater flexibility for board involvement in replacing parts of the fence and introduced an alternative rating system to enable the cost of the dog fence to be spread more equitably across landowners.

The Local Government Association gave measured support by agreeing to facilitate the collection of dog fence levies in areas where councils opted to participate on a voluntary basis. [32] Concerns with the inequity of the rating system were resolved with the decision by the newly formed Sheep Advisory Group (established under the Primary Industries Funding Schemes Act 1988) to cover the rates from the agricultural areas through their Sheep Transaction Levy.

A hole dug by a fox under the dog fence on Mulyungarie Station that would also allow access by a dingo.

Image: PIRSA

Long-term dingo electric fence trials resolved that a 10-wire sloping and a composite electric/netting design excluded all dingoes for the duration of the trials (46 and 69 months respectively). The sloping fence was recommended on the basis of cheaper construction ($2,591/km) and maintenance costs than the composite fence ($100/km less per year over 40 years). However, the composite fence ($3,602/km) was recommended for areas where soils were susceptible to erosion. [33]

10 wire straight electric dog fence adjacent to the old netting fence on Balcanoona Station.

Image: PIRSA

After trying for a number of years to have a realignment of the fence adjacent to Yandama Creek (north-east of Hawker), the proposal was finally rejected by the lessees of Quinyambie Station in August 1997. This would have removed a large cul-de-sac and resulted in substantial cost savings. The lessees required kangaroo numbers, which were at a low level due to dingo predation, to be kept at that level after removal of the dingoes but the Dog Fence Board considered this impractical and were not prepared to maintain the old fence while the dingoes were cleared out.[34]

Legislation review

Legislation review

In 1999, the Minister initiated a review of the Dog Fence Act to determine the:

- effectiveness of the Act in its present form

- relevance and powers of the Dog Fence Board

- most appropriate legislative provisions for the future management of the dog fence.

Extensive community consultation followed the distribution of a discussion paper with meetings held with those mist affected by the legislation. Amendments were not presented to Parliament until 2005 with the main change providing for secondary dog fences in addition to the primary dog fence.

Prior to this review, in November 1998, the Legislative Council appointed a Select Committee to inquire into and report upon wild dog issues in South Australia. The Committee was to report on:

- the method of raising funds for the maintenance of the dog fence with a view to making collection more equitable

- issues associated with the control of wild dogs inside the dog fence

- describing and/or quantifying other significant benefits and costs associated with maintaining the dog fence.

An interim report was tabled in June 2000. The Select Committee proposed to sit to consider reaction to the report. No formal submissions or responses were received so the Committee wrote to the Premier and Minister for Primary Industries seeking comments and advice on any issues arising since the interim report was tabled. The Premier responded in November 2001 proposing that in the main the issues raised and covered under the Committee’s Terms of Reference had been satisfied by:

- general acceptance of the revised dog fence rating system

- the planned review of the Animal and Plant Control Commission’s Policy on the Management of Dingo Populations in South Australia during 2002

- the review of the Dog Fence Act. [35]

Specific pest animals

Below is information on those pest animals which were of significance for primary producers, other landowners and the Government during the period 1971 to 2000.

Birds

Birds

With the establishment of a dedicated body related to vertebrate pests, the number of queries increased seeking advice on exotic and native birds but capacity to give advice was limited by lack of research.[36] In 1981, a project was established to define the extent and nature of damage caused by birds in orchards and to seek methods of bird control. This project looked at the mapping of orchards affected most by birds, what types of fruit was most attacked, the extent of damage, what bird species were responsible and when damage occurred. [37] This project was led by Dr Ron Sinclair. Based on this preliminary work, bird damage concentrated on cherry orchards in the Adelaide Hills. Initial research focused on the rosella, with most popular and lucrative varieties of cherries being the most severely damaged. [38]

Between 1984 and the early 1990s when the project wound down, research focussed on the economics and mechanics of netting whole orchards to exclude birds and on effective bird repellents but also included bird damage in grapes and dried fruit crops. Despite considerable effort put into promoting permanent netting of orchards as an effective, practical and economic method of bird control, it was difficult to convince growers that the high initial capital costs could be quickly recovered particularly when damage levels were high. [39] However, by the end of the 1990s, pest bird problems appeared to be increasing particularly with the dramatic expansions in the wine grape industry and in the olive industry and continuing expansions in the abundance and range of pest species, especially lorikeets and cockatoos. [40] The Department also worked with the almond industry in the Riverland to control damage caused by bird species.

During the 1990’s, a major project at the Lenswood Research Centre was initiated to develop a new intensive cherry production system comprising bird netting, tree training, modified irrigation and fertilisation. This production system achieved significant increases in yield and helped revitalise the industry.

In 1985, the provisions of the Local Government Act 1934 relating to the destruction of sparrows were repealed altogether as no longer appropriate, which they had been for some time. At about the same time there were increasing problems posed by pigeons. This species was fouling buildings including grain silos and export terminals, damaging crops, competing for food, fouling water at intensive animal raising establishments causing public health problems. Environmental problems were also becoming more noticeable through competition with native birds for nesting habitat. [41]

In 1989 a permit scheme was introduced for the control of exotic birds following extensive consultation with avicultural interests. [42] By 1996 however, the Commonwealth initiated a National Exotic Bird Registration Scheme under provisions of the Commonwealth Wildlife Protection Act. The State permit scheme modified its requirements for the keeping, selling and movement of exotic birds in South Australia to complement the new scheme. [43]

Cane toads and camels

Cane toads and camels

In 1935 cane toads were introduced to growing areas of Queensland from Hawaii to control cane beetles. They quickly spread and now occur over large areas of Queensland, north coastal New South Wales, the Top End of the Northern Territory and into Western Australia. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, cane toads began to be found in South Australia, inadvertently brought into the State in consignments of plants from Queensland.

These incidents were used to provide extensive publicity for the dangers posed by this species. Major importers of ornamental plants from northern Australia, major wholesalers and retailers of nursery plants were contacted to seek co-operation in the eradication of any cane toads found. [46] Later cane toads were found by a banana merchant at the South Australian Produce Market, Pooraka with these toads being humanely destroyed. [47]

Individual cane toads continued to be reported but were quickly identified and destroyed. In 1996 two incidents were reported of cane toads found in the wild at Victor Harbor and Paradise. An immediate response was initiated but following thorough inspections no other cane toads were found. [48] Occasional incursions of cane toads continued in produce but were appropriately dealt with.

Cane toad

Image: PIRSA

The first systematic attempt was made in 1969 to assess the number of feral camels across outback Australia. It provided an estimate of 15,000-20,000. By 1988 it was estimated that the minimum Australian feral camel population was 43,000, in a broad belt through central Australia from Broome to western Queensland. By 2008, feral camels were estimated at 1 million. [44] The effect of camels on the ecology of the rangelands was becoming much more pronounced.

In 1985, the Camels Destruction Act was no longer effective and was repealed. Up until 1996, the keeping of camels in South Australia required a permit. In that year a policy on camels in South Australia was adopted. In support of the policy the proclamation of camels was varied to allow this species to be kept without a permit but did not propose enforce control by landowners. [45]

Cats and foxes

Cats and foxes

Feral cats continued to have a direct effect on native species through predation, disease transmission and competition for resources. Feral cats also predated on rabbits.

Research was undertaken in the late 1990s monitoring feral cat and rabbit numbers in South Australia. This demonstrated a strong link between these two species with populations of both rabbits and feral cats crashing with the release of rabbit calici-virus disease in 1995. [49] By 2000, feral cats were classified as abundant and widespread over half of South Australia.

Although fox populations were known to be high throughout the State, no objective assessment had been made although anecdotal evidence indicated higher numbers in parts of Adelaide Hills, the Murray Mallee and the South East. [50] Foxes were recognised as a major predator of lambs and a potential wildlife reservoir for rabies so vertebrate pests training courses included an increased emphasis on fox control. [51]

By the 1990s several boards in areas where foxes were causing concern had provided a bait preparation service and advice for landowners. Again it was only indicative that the highest concentrations of foxes occurred in the Southeast, the Adelaide Hills and the Adelaide Plains. [52]

Fox baiting had increased dramatically by the late 1990s and a research project commenced comparing the effect on key indicators of fox control with that of other land management practices. Recommendations on the value and practice of fox control at the State, regional and local levels were compiled in 2001 and developed into an integrated extension package. [53]

Goats

Goats

Feral goat numbers were very high in the 1970s (anecdotal) but were estimated to be 380,000 in 1990 and fell to about 120,000 in 1997- the lowest level in 20 years, mainly due to commercial mustering and ground-based shooting of goats. [54]

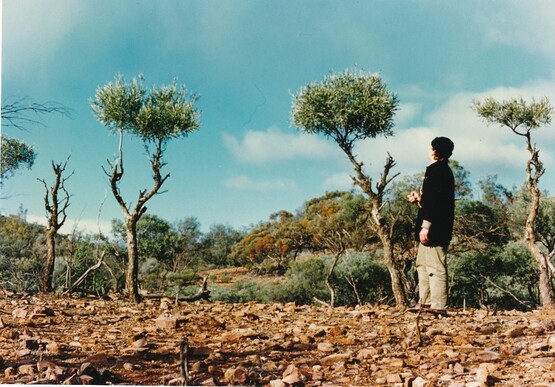

Research into the impact of feral goats on agriculture and the environment began in 1975, initially looking at their biology, including body condition, reproduction, diet and movement, and their effects of grazing in certain areas. [55] In relation to the latter, this centred on the monitoring of vegetation in the northern Flinders Ranges with exclosures, a project which was to last for some 40 years. This project was led by Dr Robert Henzell.

In 1979, aerial monitoring techniques were used in association with commercial musterers, as a method of controlling feral goats, also in the northern Flinders Ranges. The relatively high prices for feral goats had encouraged extensive mustering. At the same time, alternative methods of controlling feral goats in the Adelaide Hills commenced. [56] However, commercial mustering was only a spasmodic method to control feral goats. Although 1,600 feral goats had been removed from the Gammon Ranges National Park by aboriginal musterers in 1980, by the following year a combination of low goat densities and low prices resulted in feral goat mustering becoming uneconomical. [57]

By 1984, numbers had again increased allowing commercial mustering to resume. [58] This fluctuation of numbers and prices continues to make this method unreliable to reduce numbers. For some there was an economic incentive to let numbers build up so that mustering could continue while others perceived feral goats as a pest to be removed where at all possible.

By 1990, the number of feral goats in pastoral areas had increased, following a reduction in mustering activity. Low goat prices were due in part to the erratic supply of mustered feral goats and the resulting difficulty abattoirs and some other buyers had in scheduling goats as part of their regular operations. [59] Increasingly in the Flinders Ranges mustering was followed by shooting, from both helicopters and the ground, to reduce numbers further. [60]

Damage to mature bullock bushes from grazing feral goats, Gammon Ranges, 1995

Image: PIRSA

In the mid 1980s investigations commenced into the release of “Judas goats” carrying radio transmitters into areas known to harbour feral goats to assist in finding the herds. The Judas goats form up with the feral goats and the group could then be located with directional radio receiving equipment and the local goats destroyed. The Judas goats were then allowed to escape and the process repeated until the goats had been eradicated. [61] This method proved to be very successful and was subsequently used by other Government agencies with large tracts of land. [62] The method was also effectively used in larger tracts of native vegetation, with feral goats being eradicated by this method from the Coorong National Park. [63]

Mice

Mice

Changed farming practices, no-till and stubble retention is thought to be a major contributor to more frequent and increased mouse numbers. Soon after it was established, the Vertebrate Pests Control Authority was tasked with reviewing mouse control. A mouse plague in 1979 resulted in two staff members being redirected to begin a mouse research project. During 1979/80 a massive mouse plague occurred throughout much of the State. The worst affected areas were the cereal growing areas in Eyre Peninsula, the Mid North, Yorke Peninsula and Murray Mallee. Trials were initiated to determine the toxicity of the strychnine/wheat bait to minimise the threat to non-target species. [64]

Monitoring of 17 sites across the State in 1984 determined district mouse population changes and testing of field poisoning techniques with strychnine treated wheat began in July of that year.[65] A collaborative project with CSIRO to develop a preliminary model to predict mouse plagues commenced during 1985 and the model was confirmed the following year. [66] Trials continued and in 1990, in conjunction with previous work, demonstrated that:

- high levels of broadacre mouse control could be achieved consistently with bait laid in trails at low rates

- the area of treatment had to be larger than 250 hectares

- baiting in maturing cereal crops may be cost effective if mouse numbers were more than 150 mice per ha when the crop flowers. [67]

Mice infesting barns at Pinnaroo - 1993 mouse plague

Image: PIRSA

In 1993 the unusual seasonal conditions resulted in the worst mouse plague since 1917 and a major response was developed. Due to a lack of commercial bait product, five bait production factories were established in 11 days to help landowners combat the problem; this highlighted the effectiveness of the system of local boards guided by the Commission. Many tonnes of bait were mixed and distributed to landowners which prevented potential damage estimated at over $30 million, delivered crop production worth $40 million with a benefit-to-cost ratio in the order of 55 to 1. These estimates did not take into account the amelioration of community trauma protection afforded to the soil, or improved prospects for stubble grazing after harvest. [68]

A new system for control of mice in cereal crops was introduced in 1998 with commercially produced and distributed zinc phosphide wheat baits to replace State Government run strychnine-baiting operations. Animal and Plant Control Commission staff now provided an information conduit between landowners, agronomists, commercial bait suppliers and authorities in other states, to ensure that supplies of prepared bait were available to meet national demand. [69]

Rabbits

Rabbits

In the early 1970s, high rabbit numbers persisted throughout the State due to continued, above average rainfall. This was exacerbated by too much reliance being placed on poisoning and very little on the destruction of warrens. [70] In 1976, rabbit research covered four main areas: biology of rabbits in different climatic regions of state, extent of rabbit damage to crops, pastures and native vegetation, revised methods of rabbit control and biological control of rabbits. [71] The system of vertebrate pests control boards had likely seen, by the mid 1980s, rabbit numbers in southern settled areas fall to a low level. 1080 use had reduced to about 30% of that used in the late 1970s. Regular monitoring of rabbit numbers was being undertaken at that time, including an assessment of the status of myxomatosis. [72] However, rabbits remained a chronic problem in the pastoral areas, with conspicuous populations in the northern areas when heavy rains created conditions suitable for breeding. [73]

In 1988, the policy on the commercial breeding of rabbits was reviewed by a working group to examine the scientific and technical factors associated with commercial rabbit breeding and to evaluate the potential implications for the control of wild rabbits. The working group recommended that commercial breeding remain prohibited in South Australia. The Animal and Plant Control Commission agreed, believing that the parallels between this subject and the frustration of efforts to introduced biological control agents for the control of salvation Jane highlighted the reason why there should be no relaxation against the most serious pest animal species in temperate Australia. [74] However, after the widespread release of RCD, in 2000 the Commission revised this decision and recommended that commercial rabbit farming be permitted. [75]

Demonstration of a power fumigator using methyl bromide for rabbit warrens at the Johnburgh field day in 1992

Image: Animal and Plant Control Commission Annual Report 1992

In 1994 a series of field trials commenced on the impact of rabbits on soil erosion, degradation of native pastures and the prevention of the regeneration of native vegetation. These were conducted in conjunction with the pastoral soil conservation boards. [76] By 1997 in the Flinders Ranges, rabbits had been kept at about 10% of pre-RCD levels since late 1995 and there were significant benefits for pastoral grazing and native herbivores at the same time as recovery of native vegetation. [77]

By the end of the 1990s, rabbits continued to reduce production and environmental values in agricultural areas despite the availability of knowledge and technologies to manage this impact. An agricultural rabbit control program was initiated to coordinate efforts to seek eradication of rabbits in areas where it was considered feasible. The emphasis was on identifying and mapping potential rabbit free zones then coordinating landowner efforts to eradicate rabbits through a cooperative group approach. [78]

Rabbit fleas

Research activities continued during the mid 1970s into the use of the European rabbit flea (Spilopsyllus cuniculias) an aid to myxomatosis [79] and the breeding of fleas commenced in August 1976.[80] Following the introduction of European rabbit fleas to field sites in 1968, and a shift in the timing of outbreaks of myxomatosis to winter and early spring, there was extremely high mortality in rabbit populations. The introduction of rabbit fleas reversed the post-myxomatosis recovery of rabbits in many areas. [81]

Rabbit fleas were first released in northern pastoral areas where control work was considered uneconomical followed by the southern Flinders Ranges and the Murray Mallee during 1980. [82] Subsequent research showed that the releases in southern agricultural areas enhanced the effectiveness of myxomatosis and although there were similar benefits in the pastoral areas, the fleas had been unable to colonise in areas with less that 200mm annual rainfall. Strains from Mediterranean Europe began to be considered for possible introduction. [83]

By 1988, an extensive worldwide search by Dr Brian Cooke for improved vectors to carry the myxo virus for rabbit control identified two species of rabbit fleas in Spain with the potential to act as vectors for myxomatosis in arid areas of South Australia. [84] This was given further urgency when 1990 research work indicated that, although initially the fleas increased the effectiveness of myxomatosis, since the early 1980s there had been a steady decline in rabbit mortality observed during outbreaks of the disease. [85]

In 1993, after five years of research work, the Spanish rabbit flea (Xenophsylla cunicularis) was released in South Australia. Releases were made at a number of sites with the survival and spread of the fleas been monitored closely. Rabbit flea production continued during 1994 [86] and the fleas continued to spread at a rate of approximately 2km per year. [87]

Rabbit Calici-virus disease

RCD, now called rabbit haemorrhagic disease, is a highly infectious and lethal form of viral hepatitis that affects European rabbits. It was first recorded in China in 1984 and Europe in 1986. By 1989 initial investigations into RCD indicated that the disease had the potential for biological control against rabbits in Australia. Dr Brian Cooke conducted a study tour in Europe to look at its effects on wild rabbit populations. [88] In 1995, field trials were being conducted with the virus under quarantine on Wardang Island off Yorke Peninsula when it unexpectedly escaped to the mainland in October, 1995. A rabbit control program was activated to contain the disease on the tip of Point Pearce which is the closest point on the mainland to Wardang Island and where a rabbit killed by RCD was found. Despite an extensive effort, the control program was terminated when it was discovered late in October that the disease was already well established 370 km away in the northern Flinders Ranges. [89]

In three months, the virus spread over more than one-third of South Australia and had been detected just over the border into New South Wales and in the far western corner of Queensland. By the end of December 1995, confirmation of RCD had been obtained from as far apart as Tailem Bend, Innamincka, Marree, and Ceduna. It was also confirmed at several sites on the northern two-thirds of Eyre Peninsula, east of Port Victoria on Yorke Peninsula, at Port Wakefield and at Lewiston just west of Gawler. [90] RCD reduced rabbit numbers by 95% when it first broke out in the Flinders Ranges site in late 1995 and after some resurgence in rabbit numbers in early 1996, RCD recurred and took rabbit numbers back to the same low level as the first outbreak. [91]

Naturally recurring outbreaks of RCD continued to suppress rabbit populations, to varying degrees, throughout the State. A monitoring and surveillance program was initiated to study the impact of RCD on rabbit populations, vegetation recovery and native fauna at two sites: the Coorong National Park (coastal) and Flinders Ranges National Park (arid). An outcome of this program was to provide a better understanding of the behaviour of the disease to maximise its use by land managers in concert with conventional methods of rabbit control. [92]

It was noted in 2000 that the advent of RCD had also changed the timing of myxomatosis outbreaks from predominantly spring/summer to autumn/winter. The changes had been greatest in the semi-arid pastoral country where RCD had the greatest effect, although myxomatosis appeared to be affecting a similar proportion of rabbits as pre-RCD. [93]

Wild dogs and dingoes

Wild dogs and dingoes

The Alsatian Dogs Act was introduced in 1934 to prevent the possibility of Alsatian or German Shepherd dogs getting out of control, breeding with dingoes and becoming a threat to the sheep industry. As such Alsatian dogs were prohibited in certain parts of the State, generally within the pastoral areas and on Kangaroo Island. In 1980 the Act was amended to allow interstate travellers to obtain permits to take their dogs with them when travelling through the prohibited areas. In addition, a number of townships had been exempted from the provisions of the Act. By 1983, there was little evidence to support the claim that these dogs could breed with dingoes and become a danger to livestock. Therefore, the Act was repealed so that all breeds were subject to normal provisions of the Dog Control Act relating to the effective control of dogs throughout the State. [94]

Baiting programs for dingoes continued to be conducted inside and adjacent to the dog fence, particularly when favourable seasonal conditions resulted in an increase in dingo activity. When dingo numbers resulted in cattle losses outside the fence, baiting programs were also conducted. In the early 1970s baiting by the Department of Lands was undertaken in cooperation with the lessees, this being preferable to aerial baiting as results could be more readily assessed. [95] On-ground baiting with fresh red meat injected with 1080 was proving superior to brisket fat and strychnine baits distributed from aircraft. [96] For the remainder of the 1970s and for the 1980s baiting programs continued, varying with the number of dogs resulting from seasonal conditions and the ingress of dogs into the sheep areas following damage to the dog fence. Payments continued to be made for dingo scalps during this period.

During 1990 the Animal and Plant Control Commission decided to implement the 1975 resolution of the Vertebrate Pests Committee of the Standing Committee on Agriculture to completely phase out bonuses paid for dingo scalps. Payments ceased on 30 September after a period of widespread publicity to allow for the wind up of the scheme. Money saved was directed into the Commission's research program which was exploring methods of more effectively protecting the sheep industry, particularly from dingoes. [97] In 1970, there were 25 dingo districts remaining for registering dingoes destroyed but by 1990, when the payment ceased, this had been reduced to 15. Some 600,000 dingo scalps had been submitted since the inception of the scheme.

High dingo numbers continued in the early 1990s and baiting programs were increased in response. This was facilitated by officers of the Dog Fence Board being trained to use 1080 poison so that assistance could be provided quickly to landowners. [98] Research into the use of 1080 poison was undertaken in 1984 with the findings as follows:

- landowners were instructed to have baits as uniform as possible in size and shape

- size of baits be doubled

- average concentration of 1080 be reduced.

- landowners to be more responsible in laying baits. [99]

Further research in 1993 in conjunction with Peter Bird proposed a fundamental change in baiting strategy. Inefficient campaign baitings along the dog fence were replaced by more frequent strategic baitings using smaller numbers of buried baits targeting a 35 km buffer zone around all natural waters and watering points. [100]

By the late 1990s, dingo numbers were low outside the dog fence due to continued suppression of rabbits by rabbit calici-virus disease (RCD) and frequent buffer zone baiting campaigns. Dingo numbers inside the fence were diminishing due to targeted baiting programs and fence improvements. [101] Dingo control continued to be undertaken to protect the pastoral grazing industries by strategically reducing dingo numbers, while ensuring survival of the dingo as a legitimate wildlife species. [102]

Weed control

The Weeds Act 1956 was in force at the beginning of this period. Financial pressures in rural areas were impacting farmers’ ability to control weeds. Local government was also facing severe financial difficulties and a number of councils had dispensed with their weeds’ inspectors. This coincided with the resignation of four weed control specialists in the Department of Agriculture who were providing technical assistance to councils. To face these problems a detailed study was made proposing an entirely new scheme based on local weed control boards. [103]

This was initiated by the Minister in July 1972 with the Weeds Advisory Committee tasked to review the administration of weed control in South Australia. In July 1973 the Committee recommended:

- the continued need for weed control legislation to protect agricultural operations

- local government to play an increasingly important role in weed control administration

- pest plants other than those causing problems in agriculture needed to be included in the Act

- local government required the close support of technical services by the Department of Agriculture and local government field inspectors must be adequately trained

- multi-council boards would enable sufficiently trained personnel to be employed; urban areas were considered adequate and should not be altered

- a commission should replace the present Weeds Advisory Committee with and have certain statutory powers

- weed control on roadsides needed a complete review as its current implementation was inadequate. [104]

Weed Section Staff November 1974: Arthur Tideman, David Murrie, unknown, Peter Kloot, Grant Baldwin, Malcolm Catt, Arthur Lewis, Hon Tom Casey (Minister of Agriculture), Jim Garrick, Max O’Neil, Madge Hill, Don Canter, Ray Alcock.

Image: PIRSA

The new legislation was introduced to Parliament in 1975 with the object of providing a more effective and workable system for weed control by carrying out co-ordinated control programmes over larger areas. In addition, the Weeds Act was framed as primarily an agricultural measure and it was considered time to now include plants that were harmful to the health of the community or detrimental to the environment. For this reason, the phrase “pest plant” was introduced to replace the word “weed”, the latter thought to have limited connotations. [105]

The Pest Plants Act was based on a system comprising a central body with executive powers, the Pest Plants Commission, and a series of pest plant control boards based on local government areas. The Commission reported directly to the Minister and comprised six members, the chair being an officer in the public service who had a wide knowledge of agriculture; two public servants with knowledge and experience in pest plants and their control; two persons with extensive experience in local government and in primary production; and one to represent the interests of primary industry.

Its functions were to carry out and enforce the provisions of the Act, promote research into the control of pest plants, collate and maintain a record of pest plants within the State and develop, implement, advise on a co-ordinated programme for the control of pest plants and make payments to control boards. The Commission also had specialist staff (eight) for this purpose although pest plant research, unlike research by the Vertebrate Pests Control Authority, remained within the Department of Agriculture. [106]

The system of boards proposed under the new legislation was based on that seen by two of the Department’s officers during visits to Winnipeg, Manitoba in Canada, (Senior Weeds Officer Arthur Tideman in 1970 and Botanist Ray Alcock in 1975). [107]

The provisions imposed on landowners under the Pest Plants Act generally continued the same as under the previous Weeds Act; this included enforced control by a landowner, prohibition on the entry of pest plants into the State and movement of those plants within the State. Additional requirements were a prohibition on the sale of any goods and livestock contaminated with pest plants, and to notify control boards of the presence of certain pest plants on their land. The Commission could also declare that certain areas of the State be quarantine areas from which it would be an offence to move any livestock, soil, plants, etc.

For the purposes of the Act, three different types of pest plant were established:

Primary pest plants

these were proclaimed for the whole State, they must be destroyed, not present in the State, but known elsewhere as serious with the potential to invade South Australia or were serious pests present but destruction was practical. The plant was to be highly likely to become a significant agricultural problem or likely to have a serious adverse effect on people or their use and enjoyment of the non-agricultural resources of the State. Initially 15 plants were proclaimed.

Agricultural pest plants

Weeds of farming and grazing land that had the potential for State wide distribution or proclaimed only for parts of State where their importance was recognised. Effective control measures had to be available at reasonable cost or, if the plant was a contaminant of saleable produce, it could be effectively removed. Initially 17 plants were proclaimed for whole of State and 24 proclaimed for specified board areas.

Community pest plants

To protect community interest. Proclaimed statewide or portions of State because they were damaging to health or to protect native vegetation. Initially none were proclaimed. [108]

Pest plant legislation

Pest plant legislation

The Commission agreed that to warrant proclamation a plant must have such ability to cause damage that through its control or destruction a producer should either, in the short or long term, be advantaged in some way and effective control measures were available at reasonable cost. [109] However, the Commission was concerned at the ever-widening gap between pest plant research and boards in the field. Urgent biological studies were required on broad leaf perennials, ecological studies were required on the potential spread of pest plants and their adaptability to soil types and influence on control techniques. [110]

Golden dodder (Cuscuta campestris) infestation in irrigated lucerne near Keith 1992

Image: Animal and Plant Control Commission Annual Report 1992

Dodders (Cuscuta spp) are parasitic plants that have the ability to invade broadleaf crops and may completely destroy some. Infestations of dodder were considered seriously. Surveys were undertaken identifying golden dodder infestations along the River Murray. Two small patches of golden dodder were destroyed at Pt Adelaide and Morphett Vale and a small infestation of alfalfa dodder was treated near Lucindale. [111] Along the River Murray, local authorised officers from the Southeast and other parts of the State helped managed the dodder control program. [112]

By 1986, infestations of golden dodder were identified along the River Murray from the Victorian border to almost Lock 1. Programs to reduce its impact and spread were introduced as it was seen as one of the most serious problems in the State. To assist, the Commission purchased a boat fitted with a spray unit for riverbank control operations. Infestations of golden dodder were also found in lucerne stands in the Riverland and red dodder and Chilean dodder were found in the Southeast and eradication programs commenced. [113]

African daisy (Senecio pterophorus) had spread through large areas of the Adelaide Hills in the 1960s and by the 1970s numerous methods of treatment had been tried ranging from hand pulling and burning to bulldozing and aerial spraying. None had proved 100 per cent effective.[114] The weed continued to spread despite the significant amount of time and funding put in to controlling it and the decision was made to downgrade the program. [115] There was community uproar particularly from councils at this decision to remove African daisy from the list of noxious weeds for control and eradication. Such was the uproar that this decision was reversed by Parliament after an appeal to the Committee for Subordinate Legislation, but African daisy was later removed from proclamation following studies of the plants biology. [116]

The saleyard inspections of livestock for contamination by pest plants began in 1985. Despite some difficulties initially, inspections gained universal support with a consequential reduction in the proportion of contaminated stock being presented for sale. [117] By 1986 the Weeds Research Unit of the Department of Agriculture had three research officers investigating the biology and control of deep rooted perennial pest plants (cutleaf mignonette, skeleton weed, silverleaf nightshade and creeping knapweed), golden dodder and Calomba daisy. Other research was also undertaken into herbicidal weed control in cereals. [118]

The Pest Plants Act was replaced by the Animal and Plant Control Act in 1987, and at 31 December 1986, the number of plants proclaimed was:

- Primary pest plants – 21

- Agricultural pest plants – 19 statewide and 31 local

- Community pest plants – 2 statewide and 7 local [119]

Animal and Plant Control Commission

The Animal and Plant Control (Agricultural Protection and Other Purposes) Act 1986 was developed to repeal and replace the Vertebrate Pests Act 1975 and the Pest Plants Act 1976 and to replace them with this single Act. This provided an integrated and thus more effective system of animal and plant control under a single authority, the Animal and Plant Control Commission (further information relating to the Commission and local boards is contained under the heading of Combined Government Support Structures for Pest Animals and Weeds). [120]

As part of this legislation, a new system of plant classification was introduced. Plants were classified according to their potential threat to agriculture, the environment and public safety:

- Class 1 – whole of State. Not known to be in the State or had small infestations capable of being eradicated. Likely to become a significant agricultural problem or have an adverse effect on people or the use of non-agricultural resources. Initially 20 plants proclaimed.

- Class 2 – whole of State. Is or could become a significant agricultural problem. Effective control measures available at a reasonable cost. Initially 27 plants proclaimed.

- Class 3 – part areas of the State. Criteria same as Class 2. Initially 34 plants proclaimed.

- Class 4 – whole of State. Adversely affected non-agricultural land or the community and effective control measures were available at a reasonable cost. Initially 2 plants proclaimed.

- Class 5 – part areas of the State. Criteria same as Class 4. [121] Initially 7 plants proclaimed.

The provisions relating to the control of plants remained largely unchanged from the previous Act. However, one new provision introduced was the requirement to keep to a minimum the destruction of native vegetation. [122]

One of the first undertakings by the Animal and Plant Control Commission was to commence a review of the classification of all proclaimed plants. A continuing revision of the plant schedules was considered necessary to make the optimum use of community resources available for plant control, due to changes in plant distribution and agricultural practices.[123] The review of the classification of all proclaimed plants was completed in 1989. As a result of these reviews, policies were developed for the control of each proclaimed plant on a statewide basis taking into account the most up-to-date and appropriate technology. These policies were widely distributed to local boards through a published manual. [124]

In 1992 the discovery of branched broomrape at Murray Bridge caused concern and demonstrated that ongoing vigilance was vital to protect industry from the potentially devastating effects of exotic plants. The Commission and the Murray Bridge Animal and Plant Control Board immediately embarked on an eradication program, [125] including the branched broomrape program ().

In 1995, a discussion paper was prepared to set out amendments proposed to the Act to:

- improve the efficiency of its administration

- facilitate and encourage landowners to control proclaimed animals and plants

- encourage the integration of animal and plant control with other land management activities

- maintain a strong regulatory support for control boards.

The more major amendments proposed included:

- introducing the concept of buffer zones to facilitate animal and plant control, allowing boards the option of exempting control in a defined area

- providing consistency with and setting out links with the Soil Conservation and Landcare Act 1989

- providing that local authorised officers should meet competency standards set by the Commission

- providing that a board’s role was to encourage and assist landowners, land management groups and community involvement in coordinated programs for the destruction or control of proclaimed animals and plants. This included the development of regional animal and plant management plans. [126]

Following public consultation, a draft Bill was prepared. Further consultation ensued but the draft Bill did not proceed as its introduction to Parliament was overtaken by the proposal for legislation to integrate natural resource management in South Australia, first in 1998 and then again in 2002.

Revegetation along roadside for weed suppression developed by Iggy Honan from the Eastern Eyre Animal and Plant Control Board, Cleve ca 1990

Image: PIRSA

Developed over some time, the Animal and Plant Control Commission became a leader in developing weed risk assessment systems to prioritise coordinated control programs through the efforts of Dr John Virtue, together with CSIRO and the Queensland Department of Natural Resources. The system assessed the national significance of weeds for the National Weeds Strategy and was adapted for use with plant proclamations in South Australia, as a tool to aid prioritisation at the State and board level.

The introduction of weed risk analysis (WRA) contributed to decisions on the proclamation and importance of proclaimed species. WRA proved to be an objective and transparent system for such decisions by the Commission. [127] With this significant tool now available, a major review of plant policies was initiated with all proclaimed plants undergoing a formal risk assessment for an analysis of invasiveness, impact and potential vs current distribution. [128]

Biological control of weeds

Biological control of weeds

The hope of landowners and governments that biological control agents for weeds would be more readily available and effective came to fruition in 1971, when a rust to control skeleton weed was released in South Australia. This was the result of research started by CSIRO in 1966. The rust was not expected to eradicate skeleton weed but was expected to reduce its vigour and make other control measures more effective. [129] By the following year, skeleton weed rust was rapidly sweeping through the Mallee reducing infestations. [130] By 1978 the rust continued to be highly successful in controlling narrow leaf skeleton weed but two other skeleton weed varieties were spreading as these were unaffected by the rust. [131] Further research was undertaken by CSIRO into the mid 1990s.

Following this success more and more emphasis was placed on finding and using natural means for controlling weeds. CSIRO began a search for possible biological control agents for salvation Jane in the 1970s and a leaf mining moth was released in 1980. However, the beekeeping industry prevented further releases being made with a Supreme Court injunction. The injunction was lifted in 1988 [132] but prior to this, and in support of CSIRO, the Pest Plants Commission and control boards joined with the Department of Agriculture in making a submission to the Industries Assistance Commission (IAC) enquiry into the plant’s biological control. The IAC’s final report recommended the release of the control agents as their analyses showed that the benefits of control exceeded costs by a wide margin. [133] In 1988 the leaf mining moth (Dialectica scalariella) was released in South Australia. [134] The Animal and Plant Control Commission financially supported biological control programs for salvation Jane [135] and a second agent, the crown boring weevil (Mogulones larvatus), was released in the Mount Lofty Ranges. It was hoped that this would complement the effects of the leaf mining moth, which was well established as far north as the Barrier Highway since release in 1988. [136]

In the early 1980s, a blackberry rust was illegally introduced into Victoria and was shown to reduce the vigour of blackberry in that State. However, the Pest Plants Commission decided to wait until approved strains of the rust were available in Australia before releases would be made in South Australia. [137] That Commission made a submission to the Commonwealth Biological Control Authority in support of declaring blackberry a target organism for biological control. [138] It was not until 1992 that a blackberry rust (Phragmidium violaceum) was released at ten sites in the Mt Lofty Ranges. [139]

The Animal and Plant Control Commission provided financial support to a national project on the biological control of boneseed [140] but it wasn’t until 1993 that a black leaf-eating beetle (Chrysolina sp.) was released at Morialta and near Williamstown followed by bitou tip moth (Comostolopsis germana) in 1994 and a painted boneseed beetle (Chrysolina oberprieleri) in 1995. [141] Further financial support was provided to CSIRO initiating a biological control program for bridal creeper in 1992. A study was initiated into natural pests of bridal creeper in South Africa. [142] It was another seven years before the bridal creeper leafhopper (Zygina sp.) was officially released at four sites in the Mt Lofty Ranges. [143]

Horehound was another weed targeted for biological control. The Commission supported research by CSIRO into biological control agents from its native range in Europe and in 1994 the first agent, a plume moth (Pterophorus spilodactylus), was released at Murray Bridge and Cape Donington on Eyre Peninsula. [144] That same year, a leaf rust (Puccinia carduipycnocephali) targeting slender thistle was released at various localities in the southern Mt Lofty Ranges. [145]

Pest plant control boards

A basic principle under the Pest Plants Act was to group councils together into pest plant control boards to enable the employment of full time specialist officers so that effective weed control programs could be adopted and implemented. Single council, predominately urban, boards that could employ full time specialist officers were also considered acceptable. The Pest Plants Commission had responsibility as a pest plant control board for land outside of local government area. Many councils were keen to embrace this system and by the end of 1977 there were 14 multi-council boards and 3 single council boards established. Negotiations were underway for remaining councils to form boards as a priority. [146]

The functions of a control board were to ensure that the provisions of the Act were implemented and enforced; co-operate with the Commission and other control boards in the development or implementation of co-ordinated programmes for the control of pest plants; discharge the duties and obligations imposed upon the board by the Act; destroy all pest plants on certain lands and all public roads and travelling stock reserves within the area of the board. In addition, boards were required to publish annual lists of plants that were pest plants within its area. Boards were funded jointly by the constituent councils and the Commission. Boards were established by proclamation of the Governor with that proclamation setting out the membership of the board. [147]

By the end of 1978, 18 multi-council boards and 24 single council boards had been established [148] rising to 27 multi-council boards and 31 single council boards by December 1983. [149] One more multi-council board was established by the end of 1986. [150] However, four rural councils refused to enter into the board system to administer the Pest Plants Act despite improved technical operations and administration benefits offered by the board system. These continued to operate under the provisions of the Weeds Act [151] until finally convinced to join with the introduction of the Animal and Plant Control Act.

An analysis of the reports of pest plant boards by the Commission clearly indicated that boards were producing a service that landowners appreciated. These boards, with well qualified officers, were working with landowners in coordinating control programs thereby progressively upgrading the productivity of their properties. [152]

In 1985 the Act was amended to give pest plant control boards a clear power to enter into contracts with landowners for the control of pest plants on their land. [153] A number of boards had purchased their own spray units to help meet local spraying needs. Finance for the purchase of these units was arranged by the boards direct with lending institutions with the Commission acting as guarantor provided it could be demonstrated that the loans could be fully serviced from proceeds of board spraying activities. Loans totalling in excess of $250,000 had been negotiated by boards from 1977 to 1986 and serviced satisfactorily. The availability of these spray units together with council and private units had significantly contributed towards the control of pest plants. [154] For information on animal and plant control boards, see Combined Government Support Structures.

Specific weeds

Below is information on certain weeds which were proclaimed and had some significance for primary producers, other landowners, the Government and the general community during the period 1971 to 2000. Original and current common and botanical names are provided. The following information is sourced from declared plant policies.

Weeds (A)

Weeds (A)

African daisy

African daisy (Senecio pterophorus) is a pioneer plant that occupies bare ground after disturbance of the soil or vegetation. It may become dominant and very conspicuous in the first years after disturbance. If left undisturbed the plant gradually thins out and will not replace itself. It can occur in well managed, established pastures and cereal areas, but is not a major problem in these situations. It was first recorded in SA at Port Lincoln in 1932 and proclaimed for that area 11 years later. It spread rapidly on Lower Eyre Peninsula until about 1960, and to the Adelaide Hills and Kangaroo Island when it was proclaimed for the State in 1959. In many cases the best way of controlling African daisy is to do nothing, as it is short lived, and once other vegetation returns, it disappears. It creates an environment unsuitable for its own seedlings. African daisy was removed from proclamation in 1991.

African daisy

Image: Dept for Environment and Water

African lovegrass

African lovegrass

Image: PIRSA

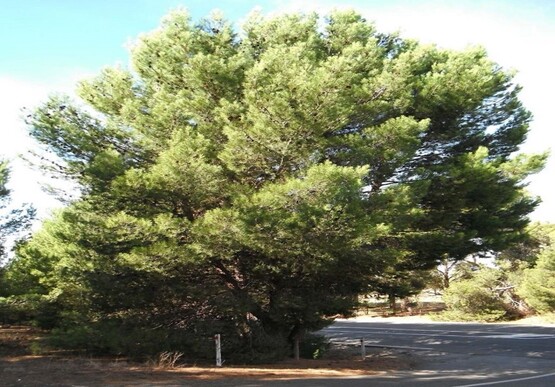

Aleppo pine

Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis) is a fast-growing tree native to the Mediterranean basin. It was introduced by settlers in the 19th century for windbreaks and as amenity plantings and has been widely planted since at least the 1920s. Aleppo pines colonise degraded or naturally disturbed landscapes, such as roadside and coastal vegetation where density of the native dominants have been reduced by grazing and other disturbances. Wind carries the seeds up to 100m from the parent plant. Shedding of the needle-like leaves forms a thick layer of mulch, which has alellopathic effects and inhibits germination of many other species. The pines also present a fire hazard. Aleppo pine was proclaimed for control on roadsides in 1990.

Aleppo pine

Image: PIRSA

Weeds (B)

Weeds (B)

Boneseed

Boneseed

Image: Dept of Primary Industries NSW

Boneseed establishes under the canopy of native vegetation where it reaches high densities in the shrub stratum under 2m tall. It displaces native species due to its dense growth. By the 1970s boneseed was recognised as an invader of bushland and was proclaimed in 1980.

Branched broomrape

Branched broomrape (Orobanche ramosa) is a root parasite on a wide range of broadleaf crops and forage legume plants. It lacks chlorophyll and only appears above ground when in flower. It has been contained in a localised area of the Murray Mallee, but is a potential threat to irrigated pasture and crops. Broomrape seed is produced in large quantities and shed in summer. The seeds are very small, but one plant can produce from 1,000 to over 200,000 seeds.

Branched broomrape

Image: PIRSA

Due to its small size, broomrape seed is very difficult to detect in produce. It can be dispersed by livestock (both internally and externally), in soil, fodder and seed for sowing, and in mud on vehicles, machinery or footwear. Contamination with broomrape seed has potential to impact on the marketability of certain products, with the small seeds industry at particular risk. Broomrapes were proclaimed in 1991.

Bridal creeper

Bridal creeper (Myrsiphyllumasparagoides) now with a revised botanical name of Asparagus asparagoides is a winter-growing, summer-dormant climbing perennial. It is highly invasive and is widespread in South Australia, invading a wide range of native vegetation communities. Controlling its spread is difficult as seed is abundant and produced in berries, which are dispersed by birds. Seedlings establish readily even in undisturbed native vegetation. Bridal creeper also spreads vegetatively via rhizomes if its root system is disturbed. Bridal creeper is a strong competitor whose dense canopy overshadows native plants and blocks sunlight during the winter growing season, greatly reducing native plant diversity.

Its large, tuberous root system competes with native plants for root space and nutrients and limits native species germination. Bridal creeper was proclaimed in 1980.

Bridal creeper

Image: PIRSA

Weeds (C)

Weeds (C)

Calomba daisy

Calomba daisy (Cenchrus macrourus), now with a revised botanical name of Oncosiphon suffruticosum, is an annual yellow flowering plant that can become a major weed of pastures. It was accidentally introduced in drought fodder from South Africa in the 1922 drought. Calomba daisy has high seed production, but its spread is slow and depends on opportunistic movement by water, hay or vehicles.

Calomba daisy

Image: PIRSA

It requires bare ground to establish and is a poor competitor. It is unpalatable to stock and also reduces the growth of pasture species by allelopathic chemicals that it releases into the soil. Calomba daisy was proclaimed in 1974.

Chilean needlegrass

Chilean needlegrass (Nassella neesiana) is an unpalatable perennial grass that invades unsown pastures or native vegetation with a grassy understorey. It is localised in South Australia and spreads by seeds, which are produced abundantly and become attached to animals, vehicles and clothing. They could also be dispersed in contaminated produce, notably hay, or be blown by the wind.

Chilean needlegrass

Image: PIRSA

Chilean needlegrass forms dense infestations in pasture, native grasslands and woodlands where it can exclude desirable species. It has low feed value to stock, and is not palatable so tends to be allowed to increase as long as more palatable pasture species are present. Chilean needlegrass was proclaimed in 2001.

Coolatai grass

Coolatai grass (Hyparrhenia hirta) is a summer-growing perennial grass that degrades pasture by forming large unpalatable tussocks. It develops as large tussocks in which the new growth is surrounded by tough, unpalatable older leaves, reducing the cover of useful forage in pasture paddocks, forms a dense cover that excludes native regeneration or growth of more palatable grasses, and carries a heavy load of inflammable older leaf material.

Coolatai grass

Image: PIRSA

It was introduced to Australia from the late 1940s to the mid 1960s as a potential pasture plant. Coolatai grass has high seed production. It spreads readily by seed, which germinates on road reserves after being carried long distances on vehicles. It may also move directly between paddocks in fodder or on vehicles and livestock. Coolatai grass was declared in 2005.

Cutleaf mignonette

Cutleaf mignonette (Reseda lutea) is a deep-rooted perennial weed of rotational broadacre cropping and pasture. It was brought to South Australia in ships’ ballast during the 19th century and has a potential to become a significant economic problem for primary production and sustainable land use in areas where it is not yet established. Cutleaf mignonette produces large amounts of seed that remain viable for 3-4 years and are spread in agricultural produce, vehicles, machinery, livestock and fodder. The extensive roots are succulent and are able to regenerate from fragments when spread by cultivation. It can establish in vigorously growing crops and pastures.

Cutleaf mignonette

Image: PIRSA

Cutleaf mignonette is an effective competitor in cereal crops, and can severely reduce yields and the cost of control is expensive. However, it is unpalatable and is only grazed when no other feed is available. Cutleaf mignonette was proclaimed in 1960.

Weeds (P-W)

Weeds (P-W)

Parkinsonia

Parkinsonia (Parkinsonia aculeata) is a thorny tree capable of naturalising in all areas of the State. It was introduced to Australia as an ornamental and shade tree in the late 1800s. Around water sources in the pastoral zone it could form large, dense impenetrable thickets that hinder access to water and make mustering difficult. The thickets shade out ground vegetation, and compete with native regrowth for water and nutrients.

Parkinsonia

Image: PIRSA