The impact is felt: 1881–1920

Introduced pest animals and weeds in South Australia – the impact is felt: 1881 to 1920 ( )

In this period from 1881 to 1920, the main response to the influx of pest animals and weeds was by legislation, with a significant number of Acts relating to pest animals but only a few for weed control. Legislation was enacted and repealed, and systems proposed, some being successful and many unsatisfactory. For a full list of all Acts relating to pest animal and weed control see Introduced pest animals and weeds in South Australia.

The material covered in this article pre-dates the introduction of metric measurements under the Metric Conversion Act 1970. Distance and weight measurements have been given in Imperial form (generally followed by metric equivalents). Also, it is an unnecessary and misleading exercise to adjust the currency from the pre-decimal pound (£), shilling (s) and pence (d). Today the value of £1 would be vastly different to the decimal equivalent of $2 when the currency was converted on 14 February 1966.

Extreme weather events

Like all decades since European settlement, this period was punctuated with extremes of weather, drought and rains, high temperatures and snow falls and violent storms. Accompanying the droughts and high temperatures there were devastating bushfires. Although there were a number of drought events during these 40 years, there were two significant periods which consisted of a series of droughts interspersed with wetter weather:

- the Federation drought from 1896 to 1902

- the 1911 to 1916 drought.

The year 1902 during the Federation drought was genuinely disastrous. Sheep and cattle over the inland pastoral districts were already starving, and so extensive was the drought that agistment was not available in any place to which transport could be arranged. The result was that sheep died in numbers that have never been equalled before or since: some sources estimate that half the sheep population was lost in the drought. This was on top of the predation from wild dogs/dingoes and foxes.

The drought of 1881 ruined thousands of farmers on marginal land in the Mid North and subsequently Goyder's Line was recognised as the limit to agricultural settlement. The following year a number of meetings were convened to aid distressed farmers and in 1883 Roseworthy Agricultural College was established as the first agricultural college in Australia with the first student admitted in 1885. This was followed in 1888 by the establishment of agricultural bureaux and in 1890 of the Pastoralists Union of South Australia.

Adapting to climatic change

In 1887 a joint Select Committee of Inquiry of both Houses of Parliament was convened into ways of encouraging farmers and small landholders to plant crops better suited to the soil and climate of South Australia in order to increase their profits, sustain employment at a more constant level and make better use of the railway lines that were being laid to carry their harvested goods to markets and storage depots. The large amount of information generated included observations on the impact of pest animals and plants. This was followed in 1898 by a Royal Commission into the declining state of the pastoral industry. For the next 70 or so years, the Government promoted interventionist strategies to stimulate and protect primary industries.

By the middle of the 1880s, approximately 1,100,000 ha of land was under cultivation and remained at this level for the remainder of the century. To assist farmers with advice, over and above that provided through the agricultural bureaux, in 1902 the Department of Agriculture was established as a science-based department. Agricultural production was severely affected from 1914 for the next five years as many workers on the land volunteered to serve overseas with Australian forces in World War 1. During this period the State’s population rose from 280,000 in 1881 to 491,000 by 1920.

Pest animal control

Control of animal pests was an arduous and necessary job for those on the land during the period from 1881 to 1920, probably the most difficult throughout the State’s history. The principal Acts relating to pest animal control in South Australia during this period are highlighted throughout the text. Mention is also made of some associated amending Acts and a few Acts with a small related provision on pest animals (such as the Crown Lands Act) may also be included.

Some Acts provided for control measures that dealt with native as well as introduced animals but this paper is restricted to introduced pest animals. Up until 1975 the word “vermin” was in general use for what we now refer to as pest animals. To avoid confusion, the term vermin has been used throughout the text below. Although certain native animals such as kangaroos, wallabies and wedge tail eagles were at various periods considered to be vermin, this article will just concentrate on those pest animals that were introduced to Australia, including the dingo which arrived in Australia from South East Asia about 3,500 years ago.

The story of pest animal control for the period 1881 to 1920 is complex and influenced by numerous Acts of Parliament which have been included under the various sub-headings below. Only the relevant provisions of these Acts that relate to the particular subject are included in that sub-heading.

If legislation came into operation and it related to a specific pest animal, a summary of the legislative provisions is included under the respective species heading. Similarly, provisions relating to vermin fencing and vermin control boards are included under those headings.

Introduced vermin

Introduced vermin

Rabbits and wild dogs/dingoes continued to cause havoc for landholders for the next 40 years and increasingly foxes and sparrows and then mice began to make their presence felt. Landholders in general were undertook what control activities that they could within their means but the problem was just too widespread for them to significantly influence singly or collectively. Many pastoral lessees ended up surrendering their leases. There were many submissions to the Government to come up with a solution and the extent of the legislative provisions enacted and their frequency of introduction to Parliament during this period shows that the Government also was unable to find an answer.

Although there was already legislation in place to suppress rabbit numbers, pressure from sheep owners had sought urgent legislation to protect their flocks. This was the Vermin Destruction Act 1882 and was mainly aimed at wild dogs/dingoes; however, rabbits were also included (as well as kangaroos, wallabies and wedge tail eagles) . This was a serious attempt to reduce the number of pest animals and the amount of damage caused by them. The Act applied to all pastoral lands outside proclaimed Hundreds, together with any other land in the colony as proclaimed by the Governor. This did eventuate and all land in the Colony was included [1].

This Act was copied from a New South Wales Act which had been found to have been effective there. Sheep owners were willing to be taxed in order to secure immunity from these animals and there was power in the Act to make a rate payable to meet the expenses of the Act. The Government made the great mistake of offering scalp bounties for pest animals. The reward offered was high and for every wild dog/dingo destroyed the sum of 10 shillings was paid and for every rabbit 2 pence. The Government acknowledged that these amounts were large but hoped to recoup funds through the increased number of sheep the land would carry following the hoped for reduction in vermin [2]. But many people took advantage of the Government’s generosity and the Treasury reeled under the expense which always remained far greater than the money collected as rates. In 1885, for example, rabbit scalps alone cost £30,000.

When this Act came into operation, the Rabbit Suppression Act 1879 continued (see Article 3 for further information on this Act). With rabbits included in the definition of vermin under the Vermin Destruction Act, there were now two Acts relating to rabbits; the former placing a statutory obligation on landholders to destroy rabbits on their land and the latter also placing a statutory obligation on landholders to destroy rabbits but also to pay a levy and then receive payment for rabbit and wild dog/dingo scalps for those animals they were required to destroy!

By 1884, the chairmen of the vermin boards outside of Hundreds had prepared a report on Government request with suggestions as to changes to the legislation based on the result of their experience. The Surveyor-General initially considered that the vermin boards be abolished altogether with a return to the original system of the Government being responsible for the control of vermin. However, the Surveyor-General and the Government concurred with the recommendations of the report in favour of retaining the system of vermin districts and boards and an amendment to the legislation was prepared based on the chairmen’s report. One of the main issues was the failure of the Government to destroy vermin on land it controlled, this being a considerable part of the pastoral lands. This had been exacerbated with a number of pastoral leases being surrendered.

The amendment in that year integrated the provisions relating to rabbits and other vermin and gave the Commissioner of Crown Lands power to compel local authorities to comply with the provisions of the Act [3]. The Government considered that if the Act was wisely administered and there was united action from all landholders then in a few years the vermin would be eradicated. This was wishful thinking given the minor changes put forward and the fact that the Government had spent £120,000 on the destruction of rabbits and other vermin in 5 years with no appreciable reduction in numbers [4].

Only one year later, a deputation of the chairmen of several district councils and vermin boards and landholders with pastoral and agricultural interests suggested vigorous Government action for the destruction of vermin in the colony. These included that:

- a central board be appointed to oversee the operations of district boards

- the administration of the Act be by boards, with district councils being merged into multi-council boards

- Government inspectors having greater powers to insist that boards act vigorously

- repairing holes in vermin-proof fences be enforced

- only wild dog/dingo and rabbit scalps continue to be paid

- natural enemies of rabbits, including cats and goannas, to be protected

- Vermin Acts of the colony be consolidated [5].

But the Government did not or perhaps could not take follow the advice provided. This was because the Government could no longer meet the expense of complying with all the requirements of the Vermin Act and urgent action was required to rein in expenditure. In the 3 years from 1882, £200,000 had been spent. Between 1 March and 31 August 1885 in Vermin District 29 (comprising the District of Dalryrnple on lower Yorke Peninsula) there were 466 dogs and 1,441,880 rabbits destroyed.

In September 1885 the Government admitted that the Vermin Act had failed and there could not be any fairer system adopted than that under the Rabbit Suppression Act, wherein owners destroyed rabbits on their land and the Government on Crown land. Legislation was introduced to Parliament to repeal the Vermin Act and revive the Rabbit Suppression Act. The Government’s idea was to immediately stop the expense by simply having the current legislation repealed, allowing the Government to administer the Rabbit Suppression Act as best it could and, at a later date, to propose improved legislation. This would take time and the Government wanted Parliament to properly consider any legislation without the need to rush something through knowing that every week’s delay was costing thousands of pounds. It was hoped that all members of Parliament would assist in developing the new legislation [6].

Despite the determination of the Government to work with the Parliament to develop better legislation it was a further 5 years before a Bill was introduced. This was likely the result of community pressure as by 1890 expenditure on vermin destruction alone had exceeded £310,000 most of which was in the interests of the pastoral industry; expenditure not justified by the results attained. Further legislation was needed [7]. Although fencing was considered expensive, by 1890 vermin destruction had cost the government £308,320 and yet there had been little, if any, discernible improvement in preventing pest animals from spreading on private property or Crown lands. [8] The Vermin-proof Fencing Act was passed in October 1890 after several months of debate.

A report to the Government had confirmed that vermin-proof fences when erected by landholders had been effective. It was also acknowledged that that the erection of fences and destruction of vermin should proceed simultaneously but landholders would be unable to undertake both on their own. The legislation provided for expenditure of such sums as might be necessary for the purpose of erecting or contributing to the erection of vermin-proof fencing and to supply wire-netting. This would give the Government power to assist District Councils and private individuals to meet the exceptional danger which threatened them.

Landholders were also required to destroy rabbits, dingoes and wild dogs in their area during the declared ‘vermin destruction months’ of February and March each year, the theory being that a concerted effort by everyone would help to reduce vermin. It may have too, if everyone did their part, but as there was little policing of the Act, simultaneous destruction periods were not a success. The law also banned the trapping or killing of any other animal that preyed on the rabbit.

The Vermin-proof Fencing Commission, appointed in 1892 'to enquire into and consider the Morgan to Winnininnie Vermin Fencing Bill and to enquire into and consider the whole question of vermin fencing', reported in 1893 and the recommendations were developed into a new legislative framework. A copy of this Vermin-Proof Fencing Commission report ( ) is available on the History of Agriculture website.

The Commission found that Crown tenants and others had to deal not merely with the vermin on their holdings, but they have been also subjected to heavy loss through being constantly restocked from neighbouring unoccupied leased or unleased lands of the Crown. Consequently, losses of stock and of rents to the Crown had been enormous and wide areas of country abandoned because of vermin and therefore the Commission was critical of inaction on the part of the Government for failing to control vermin on unoccupied Crown lands. The Vermin-proof Fencing Act was believed to be satisfactory and its maintenance desired but the inaction of the Government in allowing Crown lands to become infested was criticised.

This commenced a 5 year period where legislation relating to vermin was passed by the Parliament in each of those years. Under the 1894 Vermin Act, vermin was defined for the first time as rabbits, foxes and wild dogs. The provisions for district councils relating to loans for fence netting had worked well and a number of amendments were incorporated, mostly concerning boards and fencing [9].

The Government proposed an amendment in 1895 following the refusal of Parliament the previous year to permit any portion of the funds of the vermin boards were to be utilised for the construction and maintenance of vermin- proof fences to be used for vermin destruction. The amendment made it lawful for vermin boards and district councils to expend any portion of their rates in paying for the destruction of wild dogs and foxes. Rabbits were not included.

Councils were also able to levy a special rate not exceeding 3 pence in the pound for the destruction of wild dogs and foxes. No district council was obliged to adopt this option but could do so if desired. There were other minor amendments relating to boards and these changes amended the Vermin Act of 1894 and the District Councils Act of 1887 [10].

The 1896 amendment to the Vermin Districts Act was only 3 minor amendments related to boards and their rating (covered elsewhere) but the Government, in proposing the legislation, again emphasised that the best way of dealing with the vermin difficulty was to erect fences and destroy the vermin inside the fence rather than to try to deal with them on large un-fenced areas of country [11]. The 1897 amendment to the Vermin-proof Fencing Act was similar to the 1896 amendment in that it concerned minor amendments related to boards and rating. In making these amendments, the Government considered the operations of the Vermin-proof Fencing Act had been a success financially. The Government had advanced £49,171 for vermin-proof fencing purposes, and of that amount £16,650 had been repaid, the arrears of interest and instalments up to that time being only £195. These figures spoke strongly in favour of the system and of the safety of making the advances.

Then there was the simple but significant amendment to the Vermin Districts Act in 1898 which provided for funds raised by District Councils on rateable land to also be used for the destruction of wild dogs/dingoes in addition to rabbits and foxes. However, this could only apply when approved by the Governor. In addition, funds raised by District Councils based on the number of sheep on a property could now also be expended on fox destruction. Councils were now required to enforce the laws relating to the suppression and destruction of wild dogs and foxes as well as rabbits.

Following the release of the annual report of the Surveyor-General in September 1900, his summary of the vermin situation makes interesting reading:

In consequence of a good season rabbits are increasing very fast, and, in spite of the enormous decrease by the late drought, the plague will soon be as bad as ever if action for destruction is not carried out more unitedly. A large quantity of netting has been obtained by loans, and a considerable area under crop enclosed in various parts of the colony, which will prevent immediate damage, but the fact that certain portions are secure tends to make many of the lessees careless in clearing the pest from the land outside those enclosures. Wild dogs are said to be increasing, and pastoralists generally are alive to the fact that for protection of sheep vermin-proof fences are a necessity. There seems to be a desire on the part of some of the lessees to abolish scalping, but if this is done some other equally effective system must be resorted to, or the result will be serious. During the last twelve months only 8,242 scalps were paid for, as the price was reduced, but for the three years previous an average of nearly 17,000 dogs were destroyed each year. Had all these been left to multiply it is hard to say what would have been the present number in the colony. There are now nine vermin districts comprising an area of 10,435 square miles. The boundaries of six of them are vermin proof fenced, and others are in progress. The amount advanced to boards during the year ended June 30 was £13,088, making a total of £116,133, granted as loans to boards, district councils, and trusts. Considering the many late poor seasons, the annual instalments have been very well paid, as out of the total sum payable only £1,232 is unpaid, and two-thirds of that amount is due by trusts on the west coast, where lessees have had a bad time [12].

Later that year further amendments to the Vermin Districts Act came into operation. Most of these amendments related to boards and fences and are covered elsewhere. In 1904 new Pastoral legislation was passed by Parliament. During discussions on the legislation, it was noted that increased economic development required permanent settlement in the pastoral lands. To assist with this aim, further concessions were demanded and one of these was that the country had to be vermin-proof fenced. This was because the high price of stock prevented rapid restocking and the pastoral country could not be profitably held until it was vermin-fenced [13]. The provisions of this legislation provided for wire and netting required for the vermin-proofing of any boundary fence to be advanced to the lessee where the lessee was unable to access a loan under the Vermin Districts Act. Any such improvement paid for by the lessee was to be valued and be paid for by the incoming lessee.

Another 5 years were to pass before a revised and consolidated Vermin Act came into operation. The Vermin Act 1905 consolidated wholly or partly 15 existing pieces of legislation and added two important changes. This consolidation was necessitated following a decision by the Chief Justice in relation to an appeal against action taken by the District Council of Kanyaka against a landholder for failing to destroy rabbits. The landholder was convicted in the Magistrates Court but appealed; the Chief Justice upholding the appeal and quashing the conviction, commenting in strong terms upon the obscurity of the numerous Acts and the impracticability of administering them [14]. Enforcement virtually ceased from the date of the Chief Justice’s decision in January until the consolidated Act was passed in December.

The mass of vermin legislation was now lawyer’s nightmare. The Attorney-General admitted that no man of ordinary intelligence had much hope of understanding the Acts [15]. To illustrate this complexity, the Vermin Act of 1905 repealed and consolidated the provisions of the following Acts:

- Rabbit Suppression Act 1879

- Vermin Act Repeal Act 1885

- Wild Dog and Fox Destruction Act 1889

- The Vermin-proof Fencing Act 1890

- The Fences Act, 1892 (provisions relating to vermin-proof fences and rabbit-proof fences only)

- Vermin Districts Act, 1894 (all except section 10)

- Vermin Districts Amendment Act 1895

- Vermin Districts Amendment Act 1896

- Vermin-proof Fencing Amendment Act 1897

- Vermin Acts Amendment Act 1898

- Vermin Districts Amendment Act, 1900

- Fences Act Amendment Act, 1903 (provisions relating to vermin-proof fences and rabbit-proof fences only)

- Pastoral Act, 1904 (sections 98 to 105 inclusive and section 132)

- The District Councils Act 1887 (section 252 only)

- District Councils Amendment Act 1904 (sections 42 and 54 only).

There were two important new provisions in the legislation. One was making the Crown responsible for the destruction of vermin on its own lands but this was only within the area of district councils. For many years the Government had received numerous complaints of its failure to destroy vermin on Crown land. This new requirement was in response to those complaints but was really for show only as little Crown land was left inside council areas. The second placed the onus of proof of innocence upon the person prosecuted for failing to carry out the provisions of the legislation [16]. In addition, there was now a specific provision prohibiting introducing any vermin onto Kangaroo Island and other islands off the coast and this far sighted action has greatly assisted in keeping Kangaroo Island as well as other islands free from rabbits and foxes to this day.

The Advisory Board of Agriculture had asked the Government to go further. It had urged the Minister include in this legislation provisions relating to strict control over the introduction of birds, quadrupeds, and other animals, and of contagious diseases supposed to be effective in destroying any pests already existing in South Australia [17]. This advice was not heeded.

During the Parliamentary debate on the 1905 legislation, it was stated that altogether the Bill appeared to be a well-devised and workable instrument, and if the new provisions fail to make the law effective it will not be because insufficient powers are conferred upon the authorities who are to be entrusted with the duty of administering it [18]. However, it was only 2 years before the legislation was again amended. This was to make it easier for the relevant authorities to progress prosecutions following the breakdown of some cases due to procedural technicalities. This had followed complaints that the legislation was difficult to read and understand [19]. These and other administrative changes were quickly passed.

In 1911 further amendments to the Vermin Act was necessary. The majority of these amendments related to boards and fencing but specific power was provided for vermin boards, councils or landholders to lay poison for the destruction of vermin as required by the Act subject to appropriate signage although poison could not be laid within 100 yards (91 m) of any public road. This provision had been explicitly included to provide legal protection to landholders as prior to this a landholder had been liable for any poisonings in subsequent proceedings [20]. By this time, the Vermin Branch of the Lands Department supplied tins of SAP poison to adjoining landholders for use on Crown lands. Poison carts were also available to landholders on generous financial terms.

Again the Government found it necessary to amend the Vermin Act the following year. The Vermin Act Further Amendment Act 1912 was a simple but necessary amendment so that the Government could vary the rate of interest to be charged to boards for loans. This rate was fixed at 4 per cent, but money could not be obtained that cheaply any longer and the Government did not want to lose over these transactions [21].

Amendments to the legislation based on experience just kept coming. In 1913 additional amendments were proposed. The simultaneous vermin destruction period was increased to the first four, instead of the first three, months of the year. Boards, councils and landholders were now legally permitted to set traps to help them meet their responsibilities for the destruction of vermin. A more controversial amendment related to removing the exemption of the Act from applying to the Pinnaroo Railway breakwind. This land, comprising some 9,000 acres (36.4 km2) in all, was set aside under the Pinnaroo Railway Act 1903 to be perpetually preserved as breakwinds for the prevention of drift sand and for the conservation of the soil; the cutting or removing of timber, scrub, or undergrowth from those reserved portions was prohibited. This area subsequently became a haven for vermin. This breakwind area reverted to Crown land in 1970. The amendment required every landholder of any land adjoining the breakwind reserve to destroy all vermin on the reserve (at the landholder’s expense) together with any half width of roadside adjoining [22] . This was a significant burden on those landholders and a requirement that did not apply anywhere else in the State.

In 1914 a new Vermin Act was passed. The Government had a policy of consolidating much of the legislation that included a number of amendment Acts and given so many amendments over the previous 9 years, the Vermin Act was a prime candidate. The Vermin Act 1905, the Vermin Act Amendment Act 1907, the Vermin Act Amendment Act 1911, the Vermin Act Further Amendment Act 1912 and the Vermin Act Further Amendment Act 1913 were all consolidated into the one Act. Apart from the consolidations, there was no change other than instances in which the exact wording had been updated to give the same effect in better language where better language was deemed desirable [23]. This new Act made it easier for boards, councils and landholders and also provided a history of all changes at the end of the Act, a practice which continues to this day. The Crown Lands Act, containing provisions relating to vermin fencing and vermin destruction, was consolidated in 1915.

The drought of 1914 together with the declaration of war (World War 1) that year, had a devastating effect on cropping and livestock industries; many of those on the land also joined up to serve overseas. To provide some relief for landholders, the Government introduced legislation to suspend the operation of certain provisions of the Vermin Act and the Crown Lands Act. These related to the repayment of instalments of loans granted to district councils, vermin boards, lessees and trusts, and interest, within a specified time, as might be decided by the Commissioner of Crown Lands. The idea was that the Government, not press those bodies to which loans had been granted for repayment, and that in turn the bodies not press the lessees, who were the ultimate borrowers. The total of the arrears of the amount advanced-by the Government was about £15,000. The suspension was limited to two years [24].

A simple administrative amendment to the Vermin Act was passed in 1916 that changed certain responsibilities throughout the Act from the Surveyor-General to the Secretary for Lands. Further amendments were proposed in 1919 to make certain administrative changes such as for the collection of rates, boundary fencing and extending the time period for repaying loans but also to introduce additional obligations for some landholders. The Commissioner of Crown Lands was provided with additional powers and a simpler process to ensure that district councils, vermin boards or associated boards strictly enforced the provisions of the Act. The Commissioner, on the recommendation of a council or board, was also able to fix months other than those of January to April for the simultaneous destruction of vermin thus giving flexibility for a particular locale.

Again this legislation introduced a requirement for landholders adjoining specific Government reserves to be liable for the destruction of vermin on those reserves, this time for drainage reserves. This followed the same principle introduced 6 years earlier for the Pinnaroo Railway Reserve. Although the drainage authority was technically responsible for the destruction of vermin on the reserves, the Government ensured that it would no longer be responsible by passing the obligation to those unfortunate adjoining landholders.

Although the Vermin Act allowed for the provisions to apply for pests other than rabbits, wild dogs/dingoes and foxes, no additional vermin were proclaimed before 31 December 1920.

Specific pest animals

Below is some information on those pest animals which had some significance for primary producers, other landholders and the Government during the period 1881 to 1920.

Foxes

Foxes

By 1888 foxes had moved into the South East of the State from Victoria and were common all the way up to the Coorong where they were almost as numerous as dingoes [25]. However, councils were active in supporting landholders. For example, it was reported that in 1905 the Naracoorte and Penola District Councils had paid rewards for the destruction of 1,915 foxes, as against 551 in 1904 [26]. In an attempt to halt the spread of the fox, in 1889 the Parliament passed legislation, the Wild Dogs and Foxes Act, to introduce measures to slow the damage done to the sheep industry by wild dogs, mainly in the pastoral areas, and by foxes in the South East.

The crux of the legislation, as it related to foxes, was the introduction of a bounty for fox scalps but this only applied in respect of foxes killed upon land outside the boundaries of any corporation or district council. The scalp money would be raised by a tax imposed on the lessee of land held under lease from the Crown. This money, paid into a Fund, would then be paid out by the Treasurer for the destruction of wild dogs and foxes. There seemed to have been a general view that settlers would be willing to pay the taxes themselves rather than that there should be no measure at all. This would provide a beneficial system of organised destruction. However, others considered that the owners of sheep, the persons most interested in the matter, should contribute these taxes [27]. This bounty scheme remained in place until 1905 in the area south and east of the River Murray, having been repealed in 1900 for the remainder of the State.

The foxes were spreading north and west at an alarming rate and by 1905 were to the Fleurieu Peninsula where they were causing considerable damage among lambs, poultry and all ground birds [28]. Foxes continued to spread throughout South Australia with farmers near to Cowell noting and catching a fox in the district during 1910 [29].

Landholders were totally unprepared for this extra battle to control foxes after struggling with rabbits on top of climatic events and Government regulation. The fox problem was becoming so bad that it was realised councils would be unable to cope with the foxes as they were unable to agree on what should be done. Because of this, how to respond needed to be taken up by the State Government. One idea proposed was:

“… to tax all owners of sheep one shilling per hundred annually, and poultry owners one shilling for every 20 head…. This would form a fund, which could be placed in proper centres, no scalps being paid for, but the whole skin to be given up. This would do away with the possibility of scalp manufacture, as carried on in the past.” [30]

At the Agricultural Bureau Congress in September 1905 a large attendance of delegates from the various branches of the Agricultural Bureau discussed the problems caused by the fox, particularly in the South East of the State. There were conflicting opinions amongst sheep owners in the South East about the control of the fox. One landholder in Wattle Range, in one season alone, out of a stud flock of 200 merino lambs, had over 100 killed by foxes whereas others in the neighbourhood of Mount Gambier advertised that they would prosecute any person found destroying foxes on their respective properties as the fox was a splendid rabbit exterminator. Two resolutions relating to the fox were passed at this conference:

"That, in the opinion of this Congress, the fox is an enemy to farmers keeping sheep or poultry, and that the Government, be requested to introduce compulsory legislation for the destruction of the fox."

"That the Advisory Board of Agriculture be asked to submit this question to branch bureaus, requesting information regarding the best methods of effectively dealing with this pest." [31]

This first recommendation was included in the Vermin Destruction Act passed later that year which provided for the control of foxes (and other species) on certain lands. These measures were not enough and 10 years later the Advisory Board of Agriculture was hearing a request for the introduction again of a bounty system for fox scalps. This continued to be divisive for there were many who believed in some areas foxes were not considered a great nuisance owing to the vast number of rabbits that foxes killed. Consequently, many landholders would not take any steps to destroy them even though they had a statutory duty to do so [32]. No action resulted in relation to the introduction of a bounty on foxes.

American grey squirrels

American grey squirrels

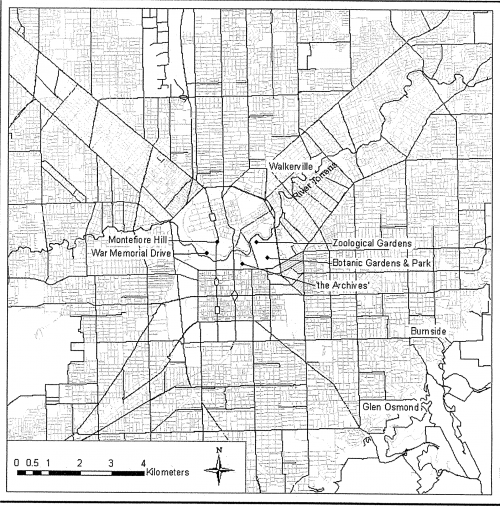

In 1919, the State Government responded to concerns from members of the public concerning the spread of, and damage to garden produce caused by, the American grey squirrel [33] in the inner eastern and northern suburbs of Adelaide. The squirrels were generally located in an area from Montefiore Hill along the River Torrens, through the Botanic Gardens and out to the suburbs of Walkerville and Burnside and down south as far as Glen Osmond. This was an area of some 40km2 however the abundance of squirrels in this area is unknown.

The likely source of this infestation was the escape of several squirrels from a resident of the eastern suburbs who had introduced them in 1917 from Toorak in Melbourne, where they were plentiful. It is also interesting to note that the Adelaide Zoological Gardens received 20 ‘American Squirrels’ in April 1917 [34] but a Government investigation in 1919 absolved the Zoo of any responsibility. The squirrels consumed nuts of various kinds and were very fond of all sweet fruits, such as apples, peaches, plums and seedling oranges together with lettuce and pine seeds.

American grey squirrel. Image: Newcastle University UK.

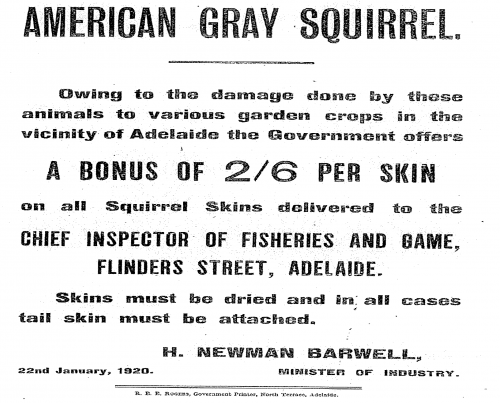

The only recommended effective means of destroying the squirrels was considered to be by shooting with a bounty paid for all skins surrendered. A bounty of 2 shillings and 6 pence per skin was subsequently set. Alternatives such as trapping would be possible but poisoning in the suburban area would be too dangerous a proposition. The advice of Government experts was that in the event of the squirrels being allowed to spread unchecked, growers would suffer serious loss, and they were unanimous that immediate action was necessary on the part of the Government to deal with the problem. Part of this action was to ask the Adelaide City Council to assist in the parklands, especially between the Adelaide Oval and the eastern boundary of the city [35].

Relatively prompt action by the Government to control the squirrels saw a bounty offered and the apparent main population controlled by the Adelaide City Council staff. It would appear that the bounty was available from 1920 until eradication in 1922 but what contribution this strategy had on the control of this pest is unknown It was also noted that the community were very aware of production losses from the rabbit and fox and this may have influenced all levels of the community to the potential threat of another introduced pest and overridden any desire to tolerate their impacts due to their aesthetic value.

The squirrels were subsequently eradicated and were last recorded in 1922. It would appear that the critical issues of suitable habitat, predation, competition and control efforts all influenced the failure of the squirrel to survive. By being restricted to urban plantings of few northern hemisphere trees and the decision of the Adelaide City Council, supported by the Government, to undertake active control by shooting the squirrels in seemingly the species’ population centre were probably both critical factors. The American grey squirrel also established in Melbourne and Ballarat but eventually died out after many decades; no active control programs were enacted in these two locations.

The points indicated on the map show the distribution of the American grey squirrel in Adelaide. Image: David Peacock, PIRSA.

1920 bounty poster for the American grey squirrel. Image: David Peacock, PIRSA.

Mice

Mice

Mice are found worldwide and the introduced house mouse probably came to Australia with the First Fleet and with many ships following. They quickly spread throughout the country and remain closely associated with human activity, especially in agricultural and urban areas. Normally population levels are relatively low, however, when conditions are favourable mice numbers can increase exponentially to plague proportions and they become a serious pest. Australia and China are the only two countries in the world where plagues of mice are known to occur [36]. Mouse numbers can build rapidly in the right conditions, leading to crop damage throughout the growing season.

Before 1880 there were small mice plagues in the eastern states as mouse numbers increased. The first “mice plague” recorded in South Australia was in the mid north in 1872 but its extent and intensity is unknown. There was damage to buildings and fittings but nothing is recorded as to damage to crops. Certainly there was a mice plague interstate.

The next plague was in 1881 where by July damage to crops was reducing as the cold weather forced mice from the paddocks into houses, barns and other places of shelter. This was followed in 1888 when ideal conditions resulted in another large plague which from reports would seem to be more severe than in 1881. Between April and August 1894, particularly in the Mid North and Yorke and Eyre Peninsulas, the mice plague of that year was even worse, with considerable damage being done to the early sown wheat crops. The plague also resulted in great damage to wheat stored on farm.

The next plague was only five years later in 1899. During this plague their effect was very noticeable in the fields, especially where the grain was sown broadcast and many farmers lost up to 30% of their crops. Even seed drilled was prone to damage as the mice burrowed. Tens of thousands of mice were killed by cats, poison and traps, which were in great demand, but these controls had little effect. Again it was only five years to the next mice plague in 1904 where the mice were playing havoc with the stored grain with one farmer reporting the loss of about 200 bags of seed wheat. The following year mice swept over the western plains of Queensland and invaded the central districts of South Australia. Mice did considerable damage at the different homesteads, station outbuildings and the boundary-riders' camps. Poisoned flour was killed many thousands but made little impact.

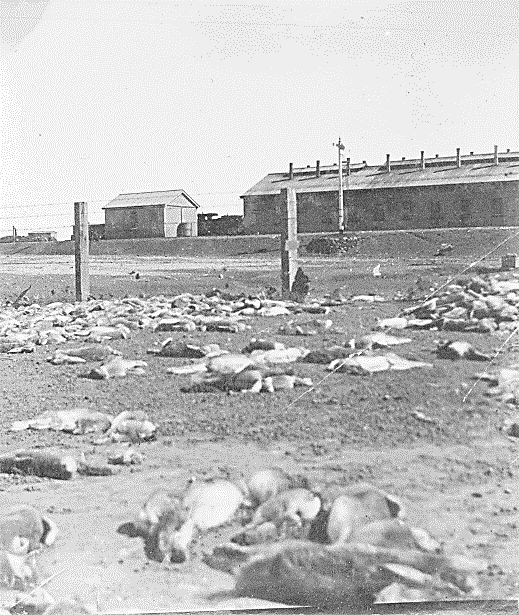

In 1911 there was a smaller, more localised plague and a more severe plague in 1916 which resulted in significant damage. However, crops were still bountiful and submissions were made to move the old crop to prevent loss and to make room for the new crop. The mice plague of 1917, however, was the largest in numbers and severity yet experienced and was one of the largest in Australia’s history. Conditions were very favourable for this event with mild weather and plenty of food following the good year of 1916. There was enormous damage done throughout the State, particularly to wheat stacks. This damage was exacerbated by the retention of a large quantity of wheat from the previous two years as the British Government was unable to furnish shipping due to the operations of German submarines around the United Kingdom. Further heavy losses to the wheat stacks occurred following the wettest season on record and a widespread weevil infestation.

Given all these factors there were calls for better protection for harvested wheat and a number of experiments were conducted with the best results coming from a double fence system trialled at Wallaroo and Port Pirie. Proposals were put in place for the erection of additional sheds, double fenced with improved hygiene and screening. These works resulted in significant improvements and a commitment from the State and Commonwealth Governments to provide for the proper storage of grain and the need for bulk handling [37].

Image: [SLSA PRG 5/15/50/6] Mice plague, Crystal Brook. Wheelbarrow overflowing with dead mice at a wheat stack, Crystal Brook: Mr FG England, conducting operations under the Harvest Board, began work on the local wheat stacks with a double-fence trap. On the first night of operations with only part of the stack fenced, Mr England succeeded in bagging 15,400 and then with the stack fenced all round, 60,000 were caught. The two catches aggregate over a ton and a quarter.

In late 1912, Parliament passed the Animals Protection Act and in May 1913 a list of animals to be protected was gazetted. In that same Gazette, a list of animals that were unprotected was also gazetted. Included in this list were rats and mice that could be destroyed at any time [38]. There is no record of whether there was any Government assistance to farmers during these mice plagues.

Image: [SLSA B 45526]. Mice damaged wheat stacks at Gulnare. There were originally 250,000 bags but 40,000 were lost. 1917.

Cats

Cats

Cats probably arrived in Australia as pets of European settlers and were later deliberately introduced in an attempt to control rabbits, sparrows and rodents. By 1890 cats had nearly colonised all of the continent, an incredible achievement. Their effect on the survival of many native species had yet to be realised.

As a biological control agent of rabbits, cats run wild (according to the terminology of the time) seemed to have had some success in controlling rabbits in the Mid North. A report from Auburn in 1882 suggests cats had suppressed rabbit numbers by taking rabbit kittens from burrows. As a result, adult numbers were decreasing and hares were taking their place [39].

As with the mongoose, there were those in the community who foresaw that releasing cats into the wild to control rabbits and sparrows would be counter productive. These people envisaged that if cats were successful they would then attack wildlife and small livestock driving settlers to despair and becoming a pest themselves [40]. A similar observation was reported for 1887 around Chalk Cliffs on the River Murray where a number of burrows were sighted but very few live rabbits. There were a number of half devoured carcasses which were later attributed to large cats, several of which were trapped and one of whose skin measured, when taken off and pegged out, two a half feet in length and eighteen inches in width (approx. 750mm x 450mm) [41]. A later report observed that during and following the 1892/93 drought, cats were habitating abandoned rabbit warrens [42].

By 1913 reports were published of the impact of cats on wildlife. Although it was too early to form definite conclusions, it was noted cats that had been in the wild for some generations, seemed to be changing to that of a blotchy colour, with a noticeable increase in size, this being especially marked in the males [43]. Cats were also being predated on by larger predators. In May 1913, a notice under the newly enacted Animals Protection Act 1912 declared that ‘domestic cats run wild’ were unprotected and could be destroyed at any time.

Image: Invasive Animals CRC

Camels

Camels

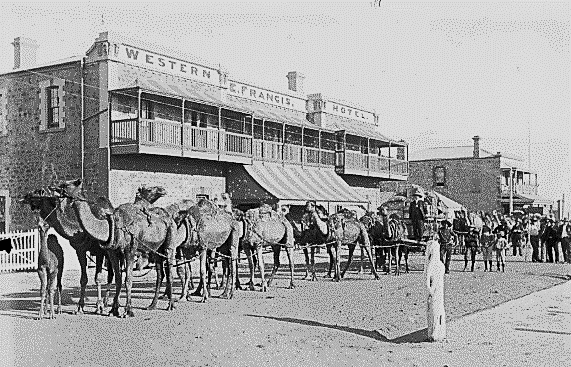

In 1839, Governor Gawler first suggested that camels [44] should be imported to work in the semi-arid regions of Australia. The first camel (the one-humped dromedary) arrived in 1840 from the Canary Islands and was used on expeditions in the mid north of the State and proved the worth of the camel in Australia’s interior. From the 1860s onward small groups of cameleers were shipped in and out of Australia at three-year intervals, to service South Australia's inland pastoral industry. Camels were well suited to working in remote dry areas and were used for riding, carting goods and as draught animals. In addition, camels continued to be used for inland exploration and in the construction of the Overland Telegraph Line.

Camel studs were set up in 1866, by Sir Thomas Elder and Samuel Stuckey, at Beltana and Umberatana Stations. Between 1866 and 1907 up to 20,000 camels were imported into Australia.

From 1920 onwards the numbers of domestic camels declined as the use of motor vehicles for freight haulage increased. As a result many cameleers returned to their home countries and some released their camels into the wild. Well suited to the arid conditions of Central Australia, these camels became the source for the large population of feral camels still existing today.

Camel teams at Port Augusta c1901. SLSA B 44761

Birds

Birds

Prior to and during the 1880s private individuals and the South Australian Zoological and Acclimatisation Society deliberately released the following exotic bird species in the hope of them establishing in the wild [45].

- Brambling

- Common blackbird

- Common chaffinch

- Common linnet

- Common starling

- European goldfinch

- European greenfinch

- Eurasian siskin

- Eurasian skylark

- House sparrow

- Red-whiskered bulbul

- Song thrush

All of these species established in the wild to some extent but only three survived to reach pest status. These were the blackbird, starling and sparrow. Individuals also imported Rock Doves, also known as common pigeons, for domestic purposes and as homing pigeons. From this small number of pigeons some escaped and established in the wild while others continued to be used for homing sport. Those that established in the wild were killed for food but in doing so homing pigeons were also targeted. This resulted in Parliament passing the Homing Pigeon Act in 1905. This was considered necessary to protect homing pigeons as they had proved themselves extremely valuable in war and the State railways benefited to the extent of several hundreds of pounds per annum by the carriage of these pigeons to the spot from which they were flown. During debate on this legislation in Parliament, the main aim was stated as being to prevent people shooting pigeons passing over their land. It remained permissible to destroy pigeons which had alighted on a farm or a garden. Homing pigeons were defined as all pigeons used as bearers of messages or as racing pigeons, identified by a rubber or metal ring on one or both legs.

But this was not the first legislation to be enacted to protect introduced birds. Prior to the introduction of the Game Act in 1886, here had been two previous Acts of the same name. All these Acts were to prevent the wanton destruction of certain wild and acclimatized animals, in particular pheasants, partridges, Californian quail and white swans. There were long closed seasons on the taking of these introduced birds and shorter closed seasons on all other introduced birds except for sparrows. Certain native birds were also protected but those native birds considered numerous or to be pests of agricultural production, such as crows, magpies, rosellas and wattle birds were exempt from protection.

Those provisions of the Game Act relating to birds was repealed and incorporated into the Birds Protection Act of 1900. This legislation was aimed at providing a specific piece of legislation for the protection of birds and followed similar legislation in other states and overseas. Protection of native birds that were useful to primary producers by destroying insect pests was a key provision but there also a closed season for certain imported game birds but no protection was provided for birds that were considered a nuisance to the producer. Imported birds not protected included English Starlings, English Chaffinches and English House Sparrows.

Sparrows

The house sparrow was first introduced to Australia in 1862 at Melbourne by the Victorian Acclimatisation Society, to import useful species. Sparrows, it was thought, could help the struggling agricultural sector. While it was known that sparrows caused some damage to fruit crops, it was hoped that this would be outweighed by the number of insect pests that the birds devoured. By today’s standards, however, efforts to ascertain the ecological and agricultural risks were very poor [46].

Sparrows appear to have been introduced to South Australia sometime after they became established in Melbourne, again in the hope they would reduce the scourge of insect pests. These birds turned out to be a significant pest damaging fruit, vegetable, grain and oilseed crops. Aesthetic problems arose as a result of faecal deposition in roosting and nesting areas with drains and gutters being blocked with nesting material [47].

Certainly by 1881 reports were appearing in the paper of the need to destroy these birds and of the effort being taken to do so. For example, fruit growers had tried wheat poisoned with arsenic but this seemed to be unsuccessful if not done correctly [48]. The efforts of those impacted by the sparrow nuisance were not enough to mitigate its effect and the pressure on the Government of the day was mounting. In response, the Government decided to appoint a Royal Commission to enquire into the damage caused by sparrows and to determine if some legislative action could be developed to deal with this nuisance.

Acting on the advice of the Commission the Government decided, in October 1881, to administratively offer a bounty for sparrow heads and eggs at the rate of 6 pence a dozen for all sparrows’ heads and 2 shillings and 6 pence for 100 sparrow heads. Payment was provided when delivered to certain police stations, post offices and railway stations with a minimum number required before payment would be made. It appears that this bounty was paid until 1885, the year the first attempt was made to introduce legislation to control sparrows. The bounty scheme cost the Government many thousands of pounds for little gain. As with most schemes of this nature, people were taking advantage of the offer by having heads and eggs collected in Melbourne and sent to them in Adelaide [49].

Representations from prominent vignerons in the Adelaide area added weight for a legislative solution and in 1885 and again in 1887 a Bill was introduced to provide measures for the destruction of sparrows but these were not passed into law. There was some opposition from members of Parliament that there was no necessity for this legislation; some considered sparrows did good as well as harm and if the community took action to control sparrows there would be no need for this type of legislation. In addition, rabbit control was considered a higher priority than sparrows or the Commissioner of Crown Lands outside of council areas. Nevertheless, the legislation was eventually passed in 1889 allowing the Governor to establish sparrow districts and providing certain duties and powers for local councils in those districts. Occupiers of land were required to destroy sparrows and hefty penalties were imposed for those who released sparrows into the wild. Inspectors appointed by councils could enter land and destroy sparrows if occupiers failed to do so.

The legislation also provided for the use of poisons to destroy sparrows and for a levy to be declared allowing funds for effectively carrying out the provisions of' the Act. The Government was of the opinion that without this legislation the destruction of sparrows would not be thorough and systematic. This legislation remained unchanged until 1921 when the Act was amended to allow the establishment of a sparrow district along a strip of land bordering Western Australia and providing that the Minister could arrange with the Western Australian Government for appointment of inspectors to that land. The Sparrow Destruction Act remained in force until 1934 when the provisions were subsumed into the Local Government Act; these provisions were not repealed until 1985.

No report on the effectiveness of this legislation has been located but up until 1895 the councils in the South East paid out the stipulated reward for 10,098 heads and 46,944 eggs [50]. However, the the damage caused by sparrows did abate. This could be because sparrows are closely associated with humans and they avoid unsettled areas and forested habitats. As towns grew and space was taken up with housing, horticultural production was pushed out to less settled areas where their impact lessened.

Ostriches

In the mid 1870s pioneer pastoralist, TR Bowman first attempted to farm ostriches in South Australia. Others also imported these birds based on the favourable reports of successful ostrich farming in Cape Colony, South Africa and the similarity of climate and land form. In 1881, W Malcom established the Barossa Ostrich farm with 7 adult birds from M. Bowman of Port Wakefield and 3 adult and 13 young birds from South Africa [51].

Landholders must have approached the Government of the day seeking support to establish an ostrich farming industry to capitalise on the demand for ostrich leather goods, hides, quality meat, feather goods – curled feathers for hats and fans, feather boas, and dusters – and eggs (there was significant economic decline in the State at this time). In 1882, Parliament passed the Ostrich Farming Act with the aim of encouraging ostrich farming. The Act allowed for Crown land to be leased within certain areas of the State at favourable rates for the purpose of ostrich farming. Individual leases were restricted to a maximum of five thousand acres (about 20 km2) with a limit of one hundred thousand acres (about 405 km2) of the State to be leased.

General view of Ostrich Farm, 7 miles north of Port Augusta c1899. Image: SLSA B 23913/15

Land leased would be for a period of 21 years with the lessee having the right to be granted the land once there were 250, one year old ostriches on the lease. The Malcolm Ostrich Company took advantage of this Act and in 1883 applied for 3,800 acres (about 15 km2) of land on the western plains, eight miles north of Pt Augusta. The flock was enlarged by the importation of a further 94 birds from South Africa, but soon after, in 1885, the South Australian Ostrich Company purchased the lease and the flock [52]. Later that year, there were 219 birds at the Port Augusta ostrich farm and a further 151 birds on a similar farm at Gawler [53]. The number of birds increased to almost 500 by 1888, despite misgivings of the enterprise from no less than the Premier of the day, with 141lb (64 kg) of marketable feathers exported [54]. Although bird numbers continued to rise, the Companyhad to contend with young birds dying from eating a poisonous plant (species not recorded), fox predation and an increase in rabbit numbers [55].

The South Australian Ostrich Company was formally wound up in 1916 after a succession of bad seasons and almost three hundred birds were moved to Priors Farm at McLaren Vale. Other ostrich farms in the State included Gawler, Noarlunga and Campbell House Station near Meningie, where there were nearly 500 birds in 1904. These farms seem to have all gone out of business by the mid 1920s.

However, on the demise of these farms not all the birds were removed. There were ostriches running wild around Meningie and the Lakes for some time after until they eventually died out. When the Port Augusta Ostrich Farm land was sold three birds were set free which continued to breed producing good batches each year but dingoes and foxes took most of the young [56]. Descendants of these birds continue to survive in the arid lands but their numbers remain sporadic and limited and are not a viable population; they are unlikely to survive in the long term.

The Ostrich Farming Act was not repealed until 1934.

Wild dogs/dingoes

Wild dogs/dingoes

Not many years after the colony was founded, domestic dogs started to run wild and these soon bred up with the dingo. Domestic dogs continued run wild and so provided an ongoing supplement to the problem. The number of wild dogs/dingoes remained a menace for the primary producer throughout the State and attempts to eradicate them both for economic and by legislative means, were largely unsuccessful.

The provisions of the Dog Act of 1867 authorised landholders to destroy unregistered dogs running wild, including dingoes. But a deficiency in the legislation was that it did not appoint any specific person or persons to enforce those provisions. A Parliamentary select committee was appointed to provide recommendations on new legislation and this took evidence, amongst other matters, on the ravages committed by dogs throughout the colony and the damage done by these animals, particularly in the pastoral districts. One pastoralist, also a Parliamentarian, the Honourable Alexander Murray considered that he had lost 100,000 sheep to wild dogs/dingoes over some 40 years [57]. The Act was amended in 1884 but with little effect. The amendments did expand the ability of a landholder so as to destroy any dog, registered with a tag or not, on that person’s land and to use poison baits, subject to certain restrictions.

In 1885 there were large packs of pure dingoes and of crossbred wild dogs preying on sheep around Port Augusta and landholders were concerned that f they found haven in the nearby Flinders ranges, then it would be very difficult to exterminate them. Sir Samuel Davenport, who owned Mount Brown Station, found the ravages of wild dogs so severe and expensive that he was determined to fence the entire station with wire netting and barbed wire fence [58]. Further east that year, 3,800 dingoes were destroyed on Paratoo Station, where many sheep had been killed.

In an attempt to provide a greater focus on wild dog/dingo control, in 1889 the Parliament passed legislation, the Wild Dogs and Foxes Act, to introduce measures to slow the damage done to the sheep industry by wild dogs, mainly in the pastoral areas, and by foxes in the South East. The crux of the legislation, as it related to wild dog/dingoes, was the introduction of a bounty for wild dog/dingo scalps but this only applied in respect of those killed upon land outside the boundaries of any corporation or district council. The scalp money would be raised by a tax imposed on the lessee of land held under lease from the Crown. This money, paid into a Fund, would then be paid out by the Treasurer for the destruction of both species.

This legislation was much anticipated by pastoralists. Even though the new legislation required a further tax, imposed at the rate of 6 pence on every square mile of land, or portion thereof, held under any lease from the Crown. The requirement for a landholder to control wild dogs/dingoes on their land remained. The legislation was relatively simple although there was some support that onlt sheep producers should be forced to pay the new tax. However, there was agreement that all pastoralists would be willing to pay the tax rather than that there would be no such specific legislation at all. A move to have the Government contribute to the Fund on account of wild dog/dingoes, and foxes, breeding on unoccupied Crown lands was rejected [59].

Again, the legislation did not work. Wild dogs/dingoes were destroyed and scalps submitted for payment of the bounty but dog numbers remained high enough to continue to menace northern flocks and caused grave concern to station owners. The subdivision of the land into vermin districts, controlled by a board, and the erection of vermin proof fencing had helped but did not provide the answer. The provisions of the Wild Dogs and Foxes Act relating to any lease situated north and west of the River Murray were repealed in 1900 and, in addition, the provisions did not apply where a lease was enclosed with an approved vermin-proof fence.

Under the Wild Dogs and Foxes Act £34,427 was paid for wild dog scalps up to 1900, and £34,778 was collected from the pastoralists by the tax of 6 pence per square mile. When the Act was repealed the arrears of taxes amounted to £1,986, and claims were in for dogs killed amounting to £1,795. With the subdivision of pastoral stations, however, it became difficult to collect the tax on the smaller holdings [60].

The Wild Dogs and Foxes Act was repealed in 1905 with the passing of the The Vermin Act (see the chapter on Vermin Control in General for more information on this and other legislation relating to wild dogs/dingoes between 1905 and 1912). Although a legislative incentive was removed in the pastoral areas, wild dogs/dingoes continued to threaten the existence of sheep flocks and the pest was more plentiful than before the Government first instituted the system of payment for scalps. This was not for the lack of effort by landholders. As an example, on one property outside a vermin district, 1,000 dogs were killed during 1909 and during the same period, in a station of less than 500 square miles (1,295 km2), 300 were killed. Sheep-breeding had become almost impossible unless something could be done by the Government to assist in the extermination of the wild dog/dingo [61].

Since 1905, but from 1900 for pastoralists, the destruction of wild dogs/dingoes was carried out chiefly by the landholders themselves, who relied largely on vermin fences to keep the dogs off their holdings. But the increase in wild dog/dingo numbers, resulting largely from the rabbit invasion where food became plentiful, significantly increased breeding and there were bigger litters together with survival rates being higher. Fences had proved of great value but as they grew old and rusty and in need of repair, dogs had penetrated the fence lines and attacked the sheep flocks. This was amplified in years of drought when food for dogs became scarce. In those drought years dogs were also bringing down calves and yearlings. On top of all this, dogs killed for sport not just food.

By 1912, pastoralists had been pressuring the Government to again introduce specific legislation to target wild dogs/dingoes. The Government reported that during the year 1911-12, a little over 6,000 dogs were destroyed. The Government also acknowledged the importance of the pastoral industry to the State and the depredations caused by wild dogs/dingoes and gave priority to introducing legislation which was hoped would protect those already engaged in the industry and encourage others to take up and develop lands currently unoccupied. The Government also anticipated that the Bill would give an impetus to the destruction of wild dogs/dingoes with every lessee having to participate in the destruction program.

The aim of the legislation was the extermination of wild dogs through the mechanism of again paying for scalps and tails from a Wild Dogs Fund. Rates were levied on certain lands to raise money for the Fund at the rate of 3 pence per square mile on land within vermin-fenced districts or which the Minister declared to be completely surrounded by a vermin fence, and 6 pence per square mile on other land. In addition, the Government provided a subsidy into the Fund of pound for pound up to £2,100pa. Scalps and tails were delivered to authorised persons for payment but only up to the total moneys available in the Fund. It was estimated that a total of £4,785 would be available annually for expenditure in connection with the destruction of wild dogs/dingoes; the Act had a sunset clause so that the Act would only remain in force until 31 December 1914.

The Minister was able to vary the payment to be made for scalps and tails so that in the event of the dogs being plentiful, a lower payment could be made, and if they were scarce, the payment could be raised. It was explained that tails were also required to prevent the possibility of fraud, as applicants had previously been manufacturing scalps [62].

The bounty system, though costly and not given to quick results, did become an incentive for landholders to destroy wild dogs/dingoes and collect the rewards. By the end of 1913, even with an extra injection of £1,000, the Fund could not cover costs. The working of the Act was examined [63]. The Commissioner of Crown Lands confidently reported to Parliament that the scalp system was the best legislation yet, with 32,000 dogs being destroyed in one year. He stressed that it continue ‘at all costs’. It certainly was reducing dingoes in the fenced districts, as no replacements could get in (for example in 1917 vermin boards received only 126 scalps in the fenced districts).

But the use of bounties was open to exploitation. Even though evidence was required when claiming the bounty, usually by way of the whole scalp of the animal, there were attempts to lodge false claims or, perhaps even worse, the harvesting of the pest species, where dingoes and wild dogs were farmed in order to collect the bounty. Scalping relied on inefficient control measures, such as shooting or trapping, that allowed the animal to be retrieved by the bounty hunter. Bounty hunting was also ineffective in resolving the pest problem in the long term as doggers, shooters and trappers would, naturally enough, only work in areas where pest numbers were high. After maximising their return in one place they would move on to another without having totally eliminated the pest animal, which would then reinfest the area.

In 1914 the Wild Dogs Act was amended to extend the operation of the Act given the three year limitation on the Government subsidising the Wild Dog Fund and for other minor amendments. The rate of 3 pence per square mile on land within vermin-fenced districts or Minister declared land was retained but the rate on other land could be determined by the Governor up to a maximum of one shilling per square mile. Other changes included removing the time limitation of the Act and introducing a minimum amount of 5 shillings for a scalp and tail. From the time of the first payments in May 1913 up to the end of June 1915, about 62,000 scalps were received.

While wild dogs/dingoes wrecked havoc on northern sheep flocks, the domestic dogs of miners and aboriginal groups were also ravaging flocks and pastoralists were seeking further controls over the keeping dogs on pastoral lands, particularly those of of miners, prospectors and wool carters [64]. However, there were no immediate changes. From the time the Wild Dogs Act came into operation until 30 September 1919 a total of 123,946 scalps and tails had been submitted for payment. The number had decreased during the war years but had risen dramatically since that time and had threatened to exhaust the Fund. The price for scalps and tails had increased to 12 shillings and 6 pence in August, 1918 but by August, 1919 was reduced to 10 shillings.

The increase in wild dog/dingo numbers forced the Government to review the financial position of the Fund owing to the extraordinary increase in the number of scalps produced during the months of April and May 1919 of more than 5,000. The Government were then faced with the position of either having to reduce the price to about 4 shillings a scalp or to advance money to the Fund. Legislation was quickly introduced that year to increase revenue of the Fund, which was to occur via two methods. The first was a one-off cash injection of £5,000 to enable payments to be continued until the rates for 1920 were available. The second method was to allow for the rating amount to be fixed by proclamation, within certain limits, and an increase in the annual Government subsidy from £2,000 to £4,000 [65].

About this time some highly original ideas for wild dog/dingo extermination were dreamed up by various would-be philanthropists. One had an interview with the Commissioner of Crown Lands with the idea of spreading folicular mange [66]. Another came from a Dutchman in Sydney who suggested dropping bombs of high density gas that he had seen used in the First World War all over the pastoral country [67]. The gas theoretically would cover the ground to the height of 3 to 4 feet enshrouding the dingoes, while the head and shoulders of a man would be above it. Not unexpectedly, these schemes were dismissed.

Rabbits

Rabbits

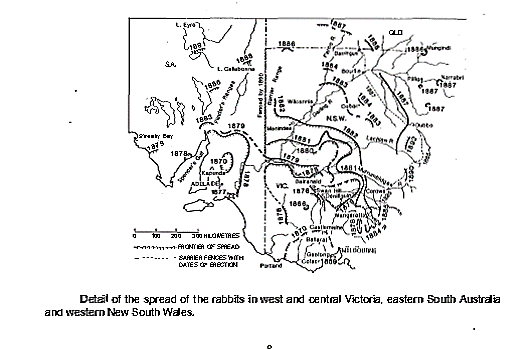

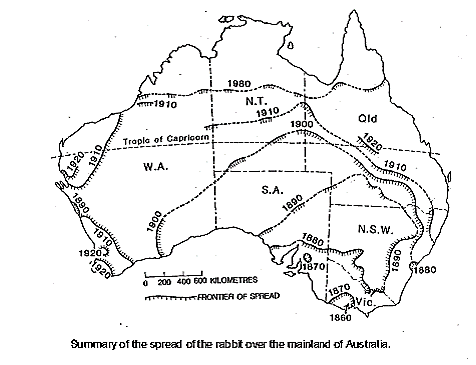

As previously related, the liberation of wild-type rabbits near Geelong in Victoria in 1859 and at Kapunda in South Australia were the two main centres of rabbit infestation in Australia. The rabbits from these two centres had merged by about 1880. The eastward spread in South Australia linked up with the north-westward spread in Victoria, forming a single block of infested country from Spencer's Gulf to the western slopes of the Great Dividing Range. The spread further northwards in South Australia is not well documented because of the sparsity of settlement, but a few records exist. They reached Beltana in 1886, Callabonna in 1888 and Lake Eyre in 1891.

The rabbit spread westward along the coast of South Australia at the same rate, 110-130 kilometres a year, as it had spread northward in New South Wales (Figure 6). In 1888 the west coast of Eyre Peninsula was listed as one of the worst infested areas in South Australia. Rabbits were 100 kilometres west of Fowler's Bay in 1893, the Western Australian border in 1894. They extended as far north as the Musgrave Ranges in SA in 1903.

Efforts to control the pest seem to have been insignificant except, perhaps, in continually disturbing the rabbit which hastened the spread. The many thousands of kilometres of barrier fences that were built to halt the spread were either erected too late or at best provided a delay of only a few years. The barrier fences acted as temporary checks, or checks on local migrations only. In the southern States attempts to control rabbits by interested graziers were nullified to some extent by trappers and others who made a profit from the newly-introduced scalp bonus system. onuses paid for scalps in New South Wales made rabbit infestations so valuable that Western Australia prohibited such payments, and a conference in Brisbane in 1888 resolved that they should be prohibited. The rate of spread of the rabbit in Australia was much faster than that recorded for any other introduced mammal anywhere in the world [68].

In all areas where the rabbit had established, the negative impact of rabbits was considerable. The rabbits suppressed the regeneration of many perennial tree and shrub species. Their local overgrazing resulted in unpalatable or undesirable plants increasing. Denudation of soil surfaces at warrens and favoured feeding grounds accelerated erosion. Rabbits competed with stock for forage and with other wildlife for habitat. They also became a major food source for wild dogs/dingoes, cats and foxes with consequent higher populations that impacted on wildlife and stock.

The colonists’ assistance in the spread undoubtedly played a part in rapid establishment of the rabbit. They had no conception of the consequences, and by the time they realised what a devastating pest had been introduced, the damage was done. The introduction of predators such as cats in an attempt to control the rabbits took no account of their possible effect on our vulnerable marsupial wildlife and on small birds which were easy prey. The erection of barrier fences was a costly and futile venture, in most cases undertaken too late and virtually impossible to maintain. The rabbit has since survived efforts to exterminate it by poisoning, trapping, shooting, disease and even by close biological studies attempting to find a flaw in its seemingly invincible armour [69].

At the time of European settlement of mainland Australia it possessed a suite of predators that preyed on rabbits, including the dingo, four quoll species and a range of raptors such as the wedge-tailed eagle, little eagle, brown falcon and swamp harrier. Establishment of villages and towns progressively eliminated the habitat of some native mammalian predators of rabbits but, more significantly, settlers sought to eliminate populations of dingoes, quolls and raptors considered to be a threat to livestock (lambs, calves) and poultry. Some researchers suggest that the advent of strychnine and its increasing use for poisoning quolls and other predators was the critical event that facilitated the uninterrupted increase of rabbit populations. Rabbits did not establish on Kangaroo Island following a deliberate release there sometime in the mid 1800s probably because of plentiful goannas [70].

It was not until the 1850s that strychnine became widely available and for the first time, local extermination of dingoes and quolls became feasible. Conversely, with the suppression of native predators of rabbits, Europeans introduced two new ones, the domestic cat and the red fox. Neither were considered, in general, to have limited the establishment of rabbits. These adverse accounts largely advocated use of rabbit poisons available at the time (e.g. strychnine, cyanide, phosphorus) which were non-selective and also killed the rabbit’s predators. On the other side of the coin, of course, rabbits were a sustainable way of living in those times. Landholders probably would not have survived as well as they did if it wasn’t for the rabbit as many of them could not afford to kill their sheep because they were in so few numbers, and so the rabbit was trapped [71].

The Rabbit Suppression Act 1879 followed two other Acts relating to the destruction of rabbits – three Acts in four years. Prior to the 1879 Act there had also been a couple of Bills which were not passed with Parliamentarians highlighting the enormous expense that would be entailed carrying out the provisions of the legislation. However, the Government of the day admitted it was struggling to find effective legislation to cope with the rabbit impact and admitted that the problem was a very difficult one to deal with. Perhaps that was why the aim/name of the legislation changed from “Destruction” to “Suppression”. Prior to this legislation, the destruction of rabbits had already cost the Government a significant amount of money, and it was acknowledged further expense would have to be incurred for a number of years. The Government considered this legislation was necessary and that the money required to implement it would be well spent.

The Government’s rabbit control parties continued to undertake work throughout the Colony but were really having little impact, despite the assertions of the Surveyor-General that they had been successful in their efforts to exterminate the pest [72]. However, there continued to be mixed opinion about the best way to destroy the rabbits with a number of people believing the Government rabbit control parties utterly unfit and next to useless — a waste of public money [73]. The main difficulty over huge areas of inland South Australia was that the settlers did not have the resources to deal with the problem. Rabbit numbers became too large for the productive capacity of the land, and their very presence in such huge numbers was then used as an excuse not to remove excessive numbers of livestock. Not only were landholders being overrun by rabbits, they also had to contend with more foxes and wild dogs/dingoes for which the rabbits were easy prey. Some landholders were eager to leave the land and one in particular was quoted as saying “I came out with nothing and I was glad to get away” [74].